Imagine Dealing with Harm Outside of Courts: A Workshop Session

On November 4, 2021, Interrupting Criminalization, Critical Resistance, and Community Justice Exchange hosted a virtual session with a small group of abolitionist organizers, lawyers, and scholars who are working to defund prosecutors' offices and criminal courts and/or are thinking about the abolition of criminal courts as part of the larger struggle for prison industrial complex abolition. The goals of the session were to (1) imagine together possibilities for exploring, evaluating and adjudicating harm beyond criminal courts, (2) generate questions for further discussion and research, and (3) inform the resources on the Beyond Criminal Courts: Divest and Defund website.

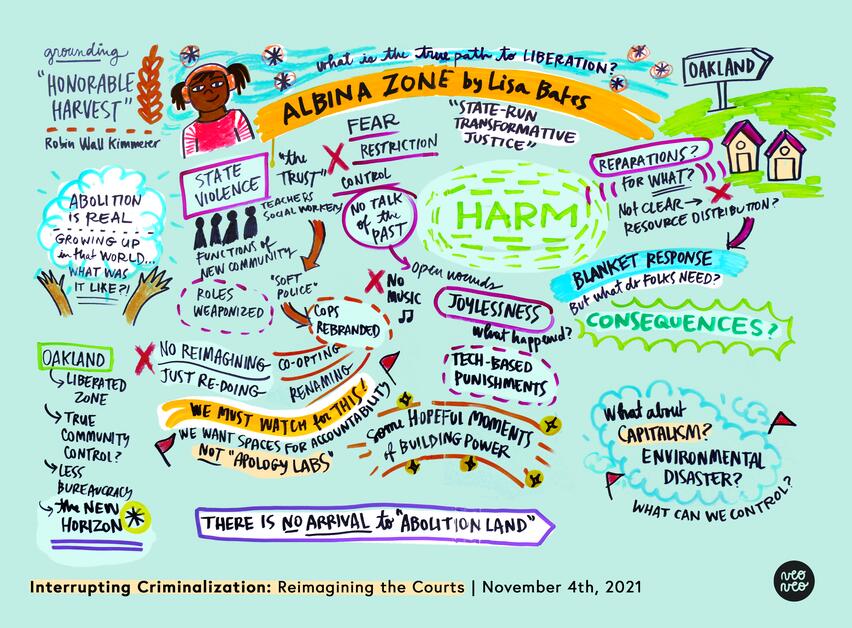

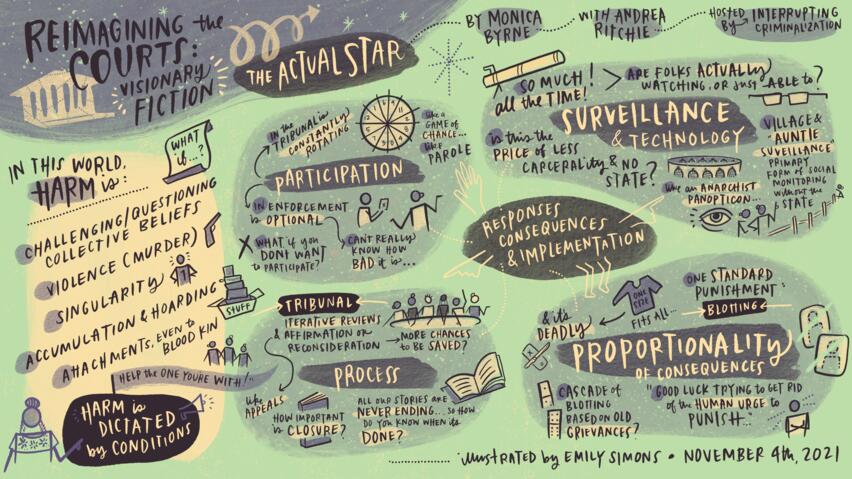

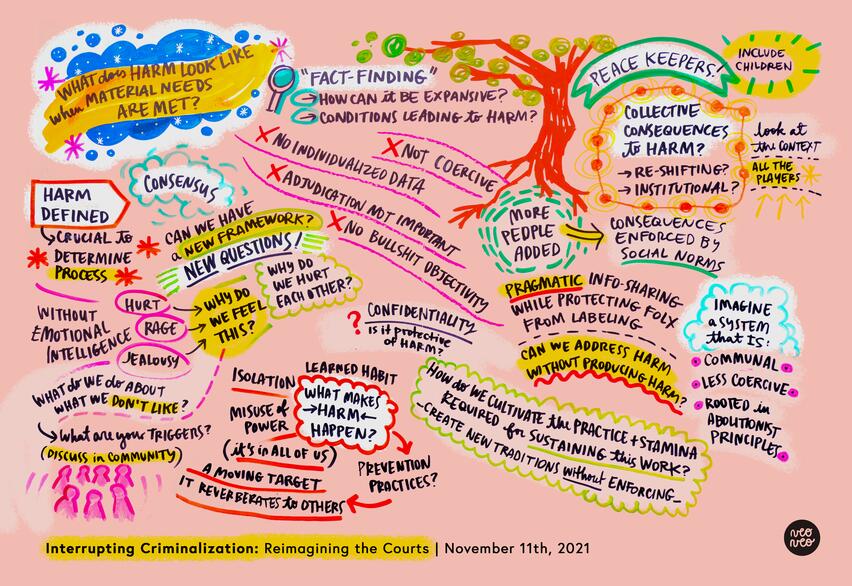

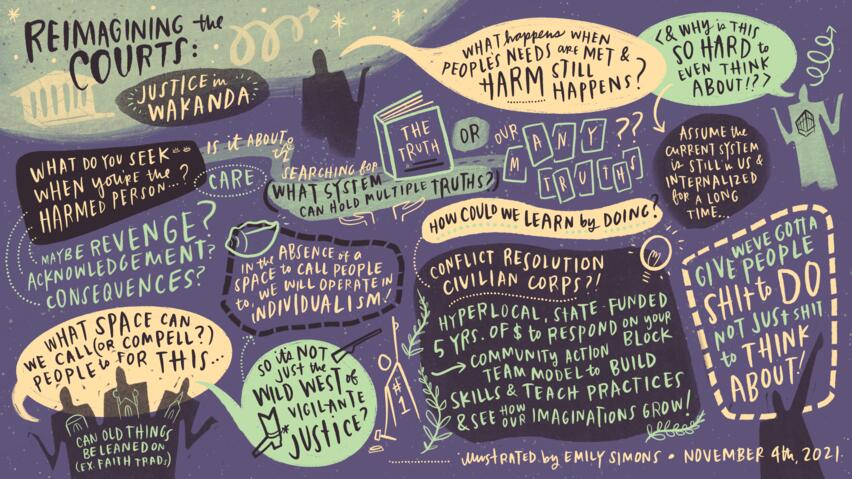

What follows is a description of a workshop developed by Andrea J. Ritchie to explore these questions, along with graphic notes and key takeaways from the November 2021 session. We offer them to illuminate some of the ways organizers are envisioning and approaching these issues, and to share the activities we used to spark imagination around these questions that can be replicated in communities.

Accessibility note: Because most of the content of the graphic notes images is covered in the text-format notes for each small group as well, we decided not to translate or offer full image descriptions for the graphic notes themselves. If you are trying to use these notes for organizing and need more extensive translations or image text descriptions, please contact us.

Welcome & Framing

As demands to divest from policing and invest in non-police community-based and accountable safety strategies have become the subject of broader discussions, several organizing campaigns have extended defund demands to include courts, prosecutors' offices, and other machinery of the criminal punishment system.

At the same time, organizers across the country continue to pursue campaigns to elect and defend "progressive prosecutors," reform bail and pre-trial detention policies, and call for establishment and expansion of court-based diversion programs.

The abolition of the prison-industrial complex necessarily requires abolition of the criminal court systems that serve as the machinery of prosecution, punishment, and surveillance, feeding people into prisons, probation, and other forms of surveillance and control. How are current campaigns moving us toward this goal? What obstacles are they facing? How are we imagining, theorizing, and practicing a world without criminal courts? What processes and mechanisms do we imagine for investigating and adjudicating harm in an abolitionist framework?

Using Visionary Fiction to Spark Imagination

We are so deeply steeped in what is, it can be difficult to step outside of it to imagine what could be. Given the stories we are told about courts as sites where justice can be done and the pervasiveness of courtroom dramas and reality shows that ingrain them as normalized features of our communities, this is particularly true of institutions like prosecutors and courts.

Using the pieces of visionary fiction linked below, we invited participants to consider the following questions:

- How is harm defined in the world described by this piece?

- Who responds? how?

- What are consequences imposed for harm?

- Who implements/enforces consequences?

“Justice: A Short Story,” in We Do This Til’ We Free Us, by Mariame Kaba

“Albina Zone” by Lisa Bates in Black Freedom Beyond Borders: Memories of Abolition Day

The Actual Star by Monica Byrne (pgs 30-54, 88-90, 136-143)

“Rememory” by Waildah Imarisha in Black Freedom Beyond Borders: Memories of Abolition Day

Of course, you can use any story, film, poem or play that resonates for you to explore these questions. For instance, Mariame Kaba often uses Junauda Petrus’ poem: Give The Police Departments to the Grandmothers to spark similar conversations.

“Justice: A Short Story,” by Mariame Kaba

Notes from the group which discussed “Justice: A Short Story,” in We Do This Til’ We Free Us, by Mariame Kaba:

- Visionary fiction disrupts what we have normalized and opens new possibilities.

- In the story, there were circles for conversation, connection, celebration and grief.

- Relationships are at the center.

- A culture of care and abundances makes harm less likely to happen.

- “I never forgot our common humanity.”

- Harm is the responsibility of the entire community, not an “individual” experience.

- How do we collectively articulate harm? How do we learn to take responsibility for when we do oppressive shit? How do we think about transforming harm at an institutional level? How do we think about the reality of the condition of grief?

“Albina Zone” by Lisa Bates

Notes from the group which discussed “Albina Zone” by Lisa Bates in Black Freedom Beyond Borders: Memories of Abolition Day:

- In the story, abolition is real, the story is told through the eyes of a young person growing up in that world - what was it like?

- Narrator contrasts the difference between Oregon and Oakland and how abolition happened differently in those places. Oakland is described as the “liberated zone” because it didn’t devolve into bureaucratic dysfunction and seemed to have true community control.

- Things that came up in the story that we must watch for: teachers & social workers as the new police (police rebranded), fear, restriction, control, no talk of the past, open wounds, no music, tech-based punishments, state-run “transformative justice.” No reimagining, just re-doing. We want spaces for accountability, not “apology labs.”

- What about capitalism? Environmental disaster? What can we control?

- There is no arrival to abolition land - we must engage in a process of constant critique to ensure that we don’t fall into carceral traps.

"The Actual Star" by Monica Byrne

Notes from the group which discussed The Actual Star by Monica Byrne (pgs 30-54, 88-90, 136-143):

- In this world harm is challenging/questioning collective beliefs, violence (murder), singularity, accumulation and hoarding, attachment, even to blood kin.

- Harm is dictated by post-apocalyptic climate refugee conditions.

- Participation in the tribunal is constantly rotating, can seem to operate like a game of chance (like parole). Participation in enforcement is optional.

- The tribunal process includes iterative reviews and affirmation or reconsideration (like appeals). It raises questions like: How important is closure? All our stories are never ending, so how do you know when it's done?

- Implementation includes (so much!) surveillance and technology.Are folks actually watching or just able to? Is this the price of less carcerality and no state? Like an anarchist panopticon? Thinking of examples of villages and “auntie surveillance,” which is a primary form of social monitoring without the state.

- Proportionality of consequences: In the story there is one standard punishment called blotting and it is one size fits all and it is deadly. Would there be a cascade of blotting based on old grievances? Good luck trying to get rid of the human urge to punish?

“Rememory” by Waildah Imarish

Notes from the group which discussed “Rememory” by Waildah Imarish in Black Freedom Beyond Borders: Memories of Abolition Day:

- In this story, everyone participates in a circle process. We all elect to uphold this system of justice everyday.

- The main character feels deep exhaustion from the circle process.

- Harm is inevitable while historical harms remain unhealed. From the story, “If he could not be healed, then what was to be done with him?” (pg 122).

- Remembering is urged and still a choice. Remembering different stages in life.

- There is a rememory waterwell where people can feel what their ancestors felt, see previous ways of dealing with harm - leads to recommitment to newer ways.

- What does justice mean in our utopia?

- Not difficult to caretake and participate in society.

- No hoarding of resources.

- Interconnected well-being.

- Less division between those who harm and those who are harmed.

- Don't have to work in order to access health care.

- When we envision the future, we bring along our past.

Wakanda Worksheet & Small Group Discussion

Imagine you are developing a new legal system for the liberated Black nation of Wakanda (as seen in the film Black Panther). That legal system must reflect abolitionist principles and reject any form of surveillance, policing, imprisonment, punishment, or exile. Assume that everyone’s basic needs for housing, food, health care (including mental health care) and liberatory education are being met, and that, for the time being at least, there are no external threats to Wakanda’s sovereignty or long term sustainability.

- What kinds of harms do you envision happening under these conditions? How would you define harm?

- What kinds of conflicts do you envision happening under these conditions?

- What kinds of fact finding do you envision when harm occurs?

- What is the purpose of gathering information?

- Who will conduct the fact finding?

- What kinds of information will be sought?

- Who will the information be presented to?

- What will be done with the information?

- What kinds of adjudication do you envision when harm occurs?

- Who will decide what should happen next?

- How will they decide?

- What if someone disagrees?

- What kinds of consequences do you envision when harm occurs?

- Who decides consequences?

- How are consequences communicated?

- What if someone disagrees?

- What if someone does not accept, abide by, or follow through on consequences?

- What kinds of supports are available to people holding and experiencing consequences?

- What collective consequences/structural changes do you imagine when harm occurs?

- How do you imagine communities learning from instances of harm about how to prevent future harm?

- Do your answers differ depending on what kinds of harm you are talking about?

This worksheet was developed by Andrea J. Ritchie based on an exercise developed by Amanda Alexander, Purvi Shah, and Marbre Stahly-Butts at the 2018 Allied Media Conference.

Notes from small groups going through this activity at the November 4, 2021 session follow.

Notes from Wakanda Justice Group #1

- What does harm look like when material needs are met?

- How can fact finding be expansive?

- What does fact finding about the conditions leading to harm look like, for example?

- Fact finding should not be coercive, no individualized data, adjudication is not important, no bullshit objectivity.

- Defining harm is crucial to determine the process.

- Can we have new frameworks? New questions? For example, why do we feel hurt, rage, jealousy? Why do we hurt each other? What do we do about what we don’t like? What are your triggers? Can we discuss these in community?

- What makes harm happen? Learned habit, isolation, misuse of power. Harm is in all of us. What are prevention practices? Harm is a moving target it reverberates to others.

- Confidentiality - is it protective of harm?

- Peacekeepers should include children.

- Collective consequences to harm? Look at the context, all the players.

- Consequences enforced by social norms.

- Pragmatic information sharing while protecting folks from labeling.

- Can we address harm without reproducing harm?

- How do we cultivate the practices and stamina required for sustaining this work?

- Imagine a system that is communal, less coercive, rooted in abolitionist principles.

Notes from Wakanda Justice Group #2

- The purpose of interventions should support a shift of consciousness from the individual to the collective, extending an opportunity to repair and take accountability. And if someone refuses that offer, they are not ready for that transformation.

- Fact finding that illuminates context and what created the possibility for that harm.

- Do not want to replicate colonial projects.

- Using our radical imagination to conjure our bigger picture. Knowing our ultimate goal allows us to take steps towards that goal.

- Even with everyone’s basic needs met, harm will still happen.

- Prisons purport to meet people's basic needs (even if they actually don't). We need to think beyond our basic needs.

- Intimate partner violence and harm is linked to state violence.

- We have internalized harms of the state.

- Harm is abuse of power and power over.

- Harm is intentional injury within a context: society, community, interpersonal, self.

- Harm is an injury to one’s power.

Notes from Wakanda Justice Group #3

- What do you seek when you’re the harmed person? Revenge? Acknowledgement? Consequences?

- Is it about searching for “the truth” or many truths? What system can hold multiple truths?

- What spaces can we call (or compel?) people to for this so its not just the wild west of vigilante justice? In the absence of a space to call people to, we will operate in individualism.

- Can old things be leaned on (for example, faith traditions)?

- What happens when people’s needs are met and harm still happens? And why is this so hard to even think about?

- Assume the current system is still in us and internalized for a long time.

- Conflict Resolution Civilian Corps: hyperlocal, state-funding, five years of money to respond on your block. Community action team model to build skills and teach practices and see how our imaginations grow.

- How could we learn by doing? We’ve gotta give people shit to do and not just shit to think about.

How do we get there from here?

Some ideas for research questions, places and opportunities to practice or experiment, and discussed detours to avoid or reforms to oppose.

- We can have an internationalist imagination, and look for example to histories of indigenous response in South Africa, politicization within South African people’s courts and histories of people’s tribunals as an onramp to organizing, creating an irresistible political vision and invitation, moving from the nuclear family to collective responsibility.

- Places and opportunities to experiment include building processes outside of courts, documenting how we already practice accountability everyday.

- Stick to the how and stay in movement and action, such as through mutual aid projects.

- Detours to avoid include: focusing on the role of public defenders, privatization of courts, diversion to family and civil courts, the middle or interim “solutions.”

- Research questions include:

- What is the history of how particular courts grew and when?

- How could we collectivize the work and responsibility of transforming harm at scale?

- What do people need to be more involved?

- How do we address the rapid expansion of reformist reforms?

- What would a different architectural space look like?

Through our visioning session we also developed a list of questions for people to consider when thinking about evaluating & adjudicating harm without courts.