Arrest

Most often, police officers make the decision about who to arrest and for what. They do not make these decisions in a vacuum however, but instead as foot soldiers of an institution designed to maintain white supremacy and protect white property.

Illusion:

The U.S. Constitution is supposed to protect people from arbitrary arrest. The 4th amendment dictates that the police can only arrest someone if they have probable cause to believe the person committed a crime. The police faithfully enforce the law and they cannot step outside the bounds of the law. When police officers make mistakes, the court system corrects those mistakes to make sure those never happen again.

Reality:

Probable cause is a very easy standard to reach, and even if police do not meet that standard there are few consequences. It is rooted in “objectively reasonable” facts known to the officer at the time of arrest—and what is deemed “reasonable” is very much shaped by race, disability, gender, immigration status. Courts, judges, and prosecutors almost always defer to police officers, and rarely second guess them.

As our comrades remind us, “Police do not enforce the law and are not accountable to it. Police make the law in every interaction by deciding who to approach, question, search, arrest, and who to ignore. Walking too fast, walking too slowly, and being stationary can all be pretexts for a police stop and police officers invoke law after the fact to justify the way that they decided to restore ‘order.’”

Here is one example:

In 2013, an undercover cop arrested Monica Jones, a Black trans woman, social work student at Arizona State University, and sex worker activist for “manifesting prostitution” after accepting his offer for a ride to a local bar.

In this case, the law itself is broad—it considers engaging passerbys in conversation and waving at cars as manifesting the intent to prostitute—and also the cop chose to target a Black trans woman and profile her as a sex worker, a phenomenon so common it is often referred to as “walking while trans.”

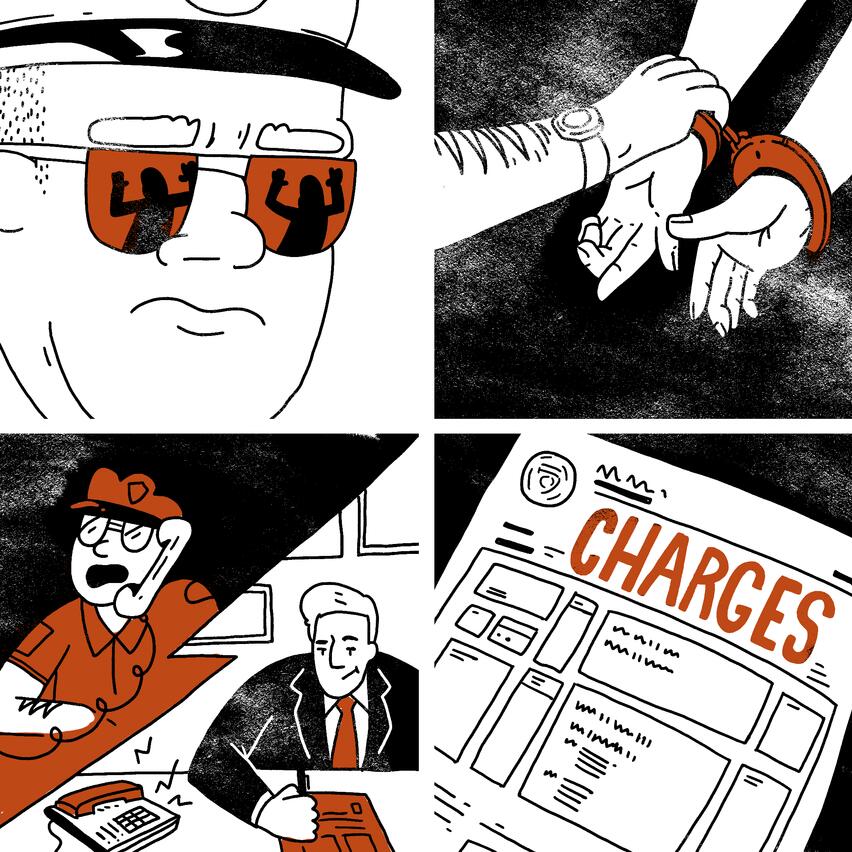

What happens after a police officer makes an arrest?

Once a cop arrests someone, they are taken to a police precinct, a central booking facility, or a jail before appearing in front of a judge or a magistrate to answer the charges against them. Depending on where (which state) and when a person is arrested (on a weekday or weekend, or in the morning or evening), they are supposed to be brought before a judge or a magistrate within 24 to 72 hours after arrest.

During this time, the cop gives their version of the event to the prosecutor, they discuss what charges the cop brought, whether there is enough information to support them, what additional charges the prosecutor might want to bring, what the cop saw or will testify to. The cop's story generally has a lot of influence over what charges are brought and how the case is prosecuted.

While the person arrested is still in police custody, sometimes the police will question them, even if they do not have a lawyer present.

This is what happened to Prakash Churaman, a Guyanese immigrant who was arrested at age 15 in Queens, NY:

Without an arrest or search warrant, police came to Churaman’s home and took him to the police precinct where they questioned and berated him for three hours without his lawyer present.

Although Miranda rights give everyone the right to ask for an attorney when they are being interrogated in police custody, many people waive their rights without knowing it (like by responding to things cops say to each other, or not expressly telling the cops that they are being silent because they are invoking their right to a lawyer, or by unwittingly talking to a police informant posing as a lawyer or arrestee), or without fully understanding the consequences of trying to talk their way out of police custody (like trying to explain what happened, or when a cop says “if you just tell us x we’ll let you go”). The result is that many confessions are forced and/or false.

Eventually Churaman confessed to being a part of a botched robbery, without even knowing that a young man was killed during this robbery. His confession allowed prosecutors to charge him with felony murder. He is still fighting the case to this day. You can listen to him tell the story of his arrest in his own words here.

Generally, the police then work with the prosecutor to ensure charges are brought against the person they arrested. Remember, it is the prosecutors, as a representative of the government, who press charges, pursue guilty verdicts, and punish, not the person who was harmed.

Illusion:

Police departments and prosecuting offices are two separate agencies with a firewall between them. Prosecutors act as a check on police, make sure all charges brought against people are legal and fair, and serve the public interest.

Reality:

Police officers and prosecutors work together throughout the entirety of a case. Police officers are investigators for prosecutors, they establish the basis for the prosecutors’ charging decisions, they serve as their key witnesses.

While prosecutors and cops have their own interests at stake, they often protect each other in the interests of keeping their jobs, maintaining each other's trust, and locking people up. Police are the eyes, ears, and boots on the ground for the prosecuting office, and prosecutors are not neutral receivers of information from the police.

Key takeaways

- By choosing who, and who not, to stop and arrest, police make the law, they are not accountable to it. There are rarely any consequences in criminal courts for cops who don’t follow the rules.

- Police and prosecutors work together and need each other for their jobs to matter. Prosecutors are not a check on police power, but an extension of it.

- The best way to reduce the number of arrests is to reduce the power of police to make them - by working to defund, divest from and abolish police, decriminalize, and to make deep investments in meeting individual and community needs to prevent, interrupt and heal from violence and harm. Learn more at defundpolice.org.