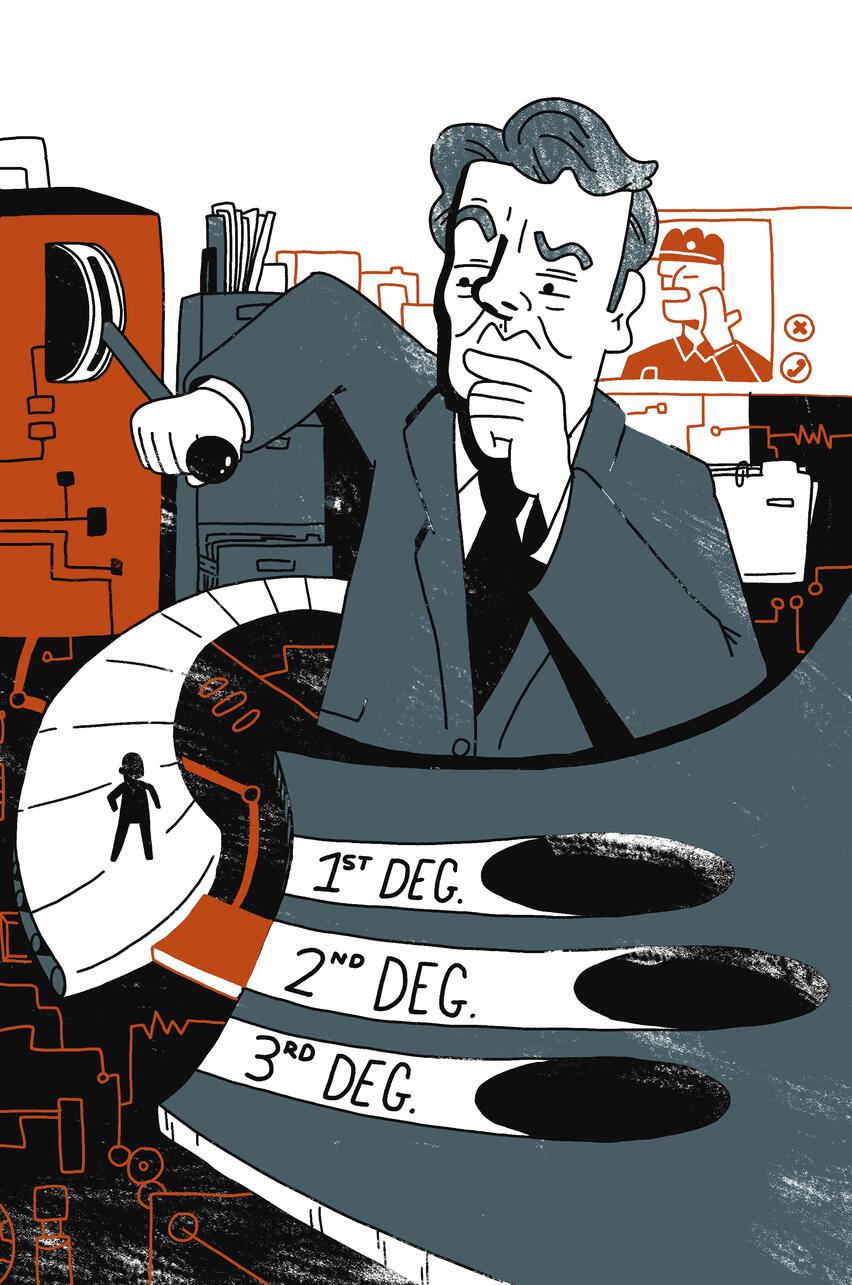

Charging

Prosecutors look at the information the cops provide and decide whether to formally charge someone with a crime. This decision helps to transform an incident into a criminal case and sets in motion the criminal court proceeding.

Illusion:

The prosecutor makes their charging decisions in an objective and careful manner, based on research and multiple sources. Their primary motivation is to protect the public interest.

Reality:

Prosecutors make their charging decisions mostly based on what the police tell them, even though police officers often make trumped up or sometimes entirely false accusations. They are motivated to rack up convictions to advance their careers.

Police lie routinely. One well known example is the police report of George Floyd's death:

The Minneapolis Police Department’s initial description of George Floyd’s death, in May 2020, said Floyd had died after a “medical incident during police interaction.”

That account was refuted within hours as the gruesome video of his death flooded the internet, igniting massive uprisings in the streets.

Prosecutors will charge any and all crimes that could conceivably be charged based on what a cop or witnesses describe. Often, many different criminal laws can cover one particular behavior (for example, taking something from a store). This gives the state a lot of power when deciding which charges to bring for the same behavior.

Take this case from New York City:

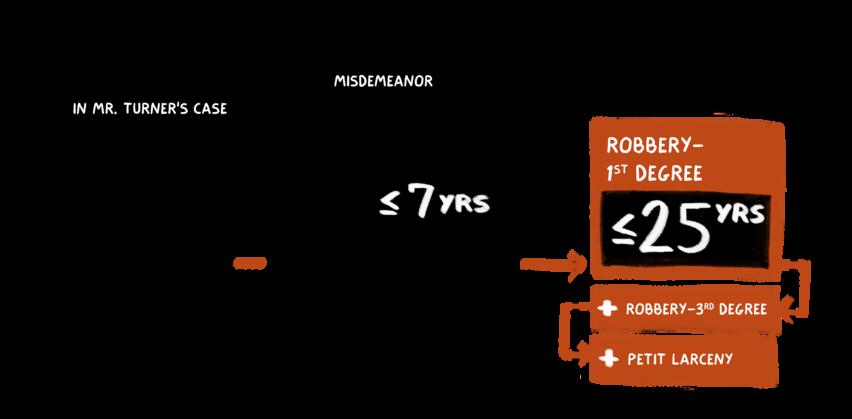

Police arrested an unhoused man named Genoly Turner living in a shelter in the upper west side of Manhattan, New York for allegedly attempting to steal bed comforters from a HomeGoods department store and threatening an employee at the store (no weapons were found on him at his arrest).

Given the allegations of what happened, the Manhattan District Attorney could have chosen to charge Mr. Turner with Robbery in the Third Degree, a felony which comes with possible 7 years prison time, or Petit Larceny, a misdemeanor which comes with up to one year in jail.

Instead, the prosecutor chose to charge him with Robbery in the First Degree, which is classified as a violent felony and comes with up to 25 years in prison. And beneath this top charge (top because it comes with the most serious punishment), the prosecutor tacked on additional, lesser charges (lesser because they come with less punishment), including Robbery in the Third Degree and Petit Larceny.

Prosecutors often have many different charges to choose from, which come with a vast array of punishment options. This amount of choice is on purpose—it allows the criminal punishment system to impose different consequences for different people and different circumstances—often in ways that discriminate based on race, gender, disability, poverty, immigration status, etc. What you are charged with determines how severely you may be punished at the end of your case. Prosecutors have full discretion over what and how many charges to bring against the person they are prosecuting.

Here is another real life example from New Orleans:

In 2010, Black feminist organization Women With A VisionOpens in new tab began to call attention to the devastating impacts on Black women, queer and trans people of prosecutors’ charging decisions for prostitution-related offenses which led to disparities in sentencing and collateral consequences, including sex offender registration.

Although Louisiana already had laws against prostitution, and oral and anal sex, since the early 1800’s (both misdemeanors), another law was passed in 1982Opens in new tab, called “Crimes Against Nature by Solicitation,” or CANS, which doubled down on both and made the acts felonies.

In 1999, after a New Orleans cop asked Wendi Cooper, a Black trans woman, to trade sex for money, he arrested her for sex work. For the same conduct, prosecutors in Wendi Coopers case could have charged her with prostitution, a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of $500 or a jail sentence of up to six months, but instead charged her with CANS, which for a first offense, was punishable by up to five years with hard labor and being put on the sex offender registry. For a third offense, you could get 20 years to life.

Why would a prosecutor tack on additional charges?

Convictions lend legitimacy (and drive more power and funding) to prosecuting offices. Piling on charges (known as “overcharging”) also increases the chance of conviction; even if one or two of the charges are dismissed, there are still a number of other charges a person can be convicted of.

A clear example of overcharging is the Bronx 120 prosecution:

In April 2016, hundreds of NYPD officers and federal agents from the Department of Homeland Security, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives raided a public housing project in the Bronx, resulting in 120 indictments on federal conspiracy charges of mostly young Black and Latino men in their late teens or early 20s. Some were already serving time for the same charges in state court.

But federal prosecutors also wanted some action. They leveled conspiracy charges, some of which were under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. These are notoriously difficult to fight in court and can come with draconian sentences.

Threatened with decades in prison, 115 of the 120 men took plea bargains to lesser charges and sentences, and only two took their cases to trial. 35 defendants were convicted of RICO or narcotics conspiracy simply for selling marijuana, which is now legal in NYC, and at least 50 were not even alleged to be gang members.

Since over 90% of convictions end in a plea, overcharging also gives the prosecuting office enormous leverage in plea negotiations. Charges with extremely long sentences discourage people from exercising their right to go to trial because they risk a longer sentence if convicted by a jury than if they accept a lower charge and sentence. Instead, a person is more likely to plead guilty to avoid loss of housing, family, children, immigration consequences that come with a lengthy incarceration. More on plea bargains soon!

Besides providing leverage for ensuring a guilty plea, why else do the prosecutor’s charging decisions matter so much?

The charges chosen by the prosecutor matter because they each come with different possibilities for punishment. Punishment does not only come in the form of incarceration. A felony conviction—or even certain misdemeanor convictions, like “prostitution-related” offenses—also have severe implications for housing, benefits like food stamps, employment, risk of deportation, parental rights, and exercise of civil rights like voting and serving on a jury.

Illusion:

If you are arrested and charged with a crime, you know exactly what you are being charged with and why.

Reality:

When the prosecutor decides the charges, they list them on a piece of paper called the complaint (also known as the accusatory instrument or charging instrument). Although the complaint is supposed to put the person on notice of the accusations, in reality, it is usually a vague document that includes very minimal facts about the crime the person is accused of having committed.

Because prosecutors only have to lay out the minimum amount of information required to make an accusation, the person being prosecuted and their defense lawyer often know very little about what the prosecution claimed happened, what evidence they have and how they are likely to use it, and therefore how likely they are to be convicted. Leaving the defense in the dark is a tactic prosecutors use as it gives the prosecution an advantage from the get go.

Key takeaways

- Prosecutors prosecute people on behalf of the government, not the person who was harmed (if there was one). This means that even if the person who was harmed doesn’t want anyone charged or if they don’t want to participate in the prosecution, the prosecution can still proceed.

- Prosecutors are entirely responsible for the charging decision. They have the power to decide whether to prosecute someone and what charges to prosecute them for. Much of their decision is based on reports from police officers, their eyes and ears on the ground.

- So much behavior in the United States is, and can be, criminalized, and the penalties are often very stiff. Average sentences in the United States are longer than many countries. Legislators have given prosecutors the tools to flex their power. Across the country, organizers have started campaigns to decriminalize offenses, such as sex work, drug possession, and poverty—that is, campaigns to change what is criminalized in order to reduce the power of prosecutors, police and the criminal punishment system to arrest, charge, and convict people.

- Structurally the criminal legal system is set up in a way that makes it more likely for a prosecutor to be able to secure a conviction if they overcharge and upcharge people. This is not just about prosecutors abusing their power, the system is designed for them to make those decisions.

- The best way to address prosecutor power is to work to reduce it, as well as the resources prosecutors' offices have, NOT investing greater legitimacy and funding into the office through campaigns to elect "progressive prosecutors" - check out the resources on targeting prosecutors’ power and resources and on defunding courts and prosecutors for more information.