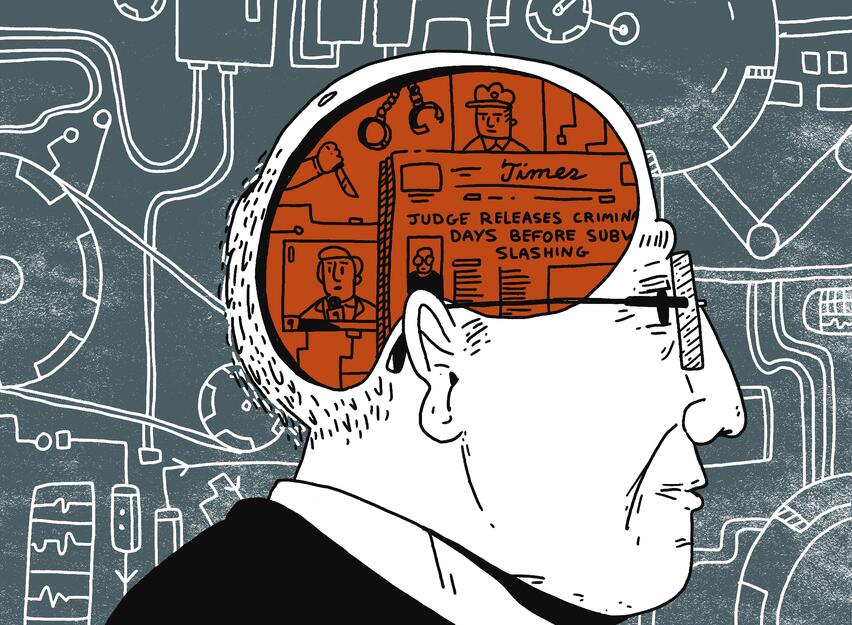

Arraignment

The arraignment is the first appearance before a judge and is the beginning of the criminal case from the court’s perspective. Arraignments are often very quick hearings, usually happening in five minutes or less, even though very important decisions are made.

Illusion:

You get a lawyer just by asking for one and you have enough time to confer before any judge makes a decision.

Reality:

Before any person accused of a crime sees the judge at their arraignment, they generally meet with their lawyer first. If the person facing charges cannot afford a private attorney, in most places they will be assigned a public defender, who are defense lawyers paid for by the government. This first meeting with a defense lawyer at the arraignment is typically very short: usually the defender will only be able to share the official charges and what the charges might mean for bail and potential plea bargains.

Whether you get a lawyer at arraignment can vary widely by place, however. For example, in places like Wisconsin or Louisiana, where the bar to getting a free attorney is so high, people without resources can wait months (typically in jail) before actually securing a lawyer.

There is a widespread misunderstanding that a person will automatically get an attorney after they are arrested based on their Miranda rights. That is not 100% accurate. You are only entitled to an attorney immediately after your arrest if (1) the police want to question you, and (2) you assert your right to an attorney. Just because you have the right to a lawyer during police questioning, doesn’t mean you will actually have access to one.

There are two primary purposes to the arraignment:

- OFFICIAL CHARGES: The person arrested finds out what they are officially being charged with by the government (i.e. the prosecutor);

- CASE ENDS OR CONTINUES: The case either ends through the prosecutor dismissing the charges or through a guilty plea. The other option is that the case continues and the judge decides conditions of release (also known as bail).

1. OFFICIAL CHARGES

One of the first decisions a judge makes is about whether there is a legal basis for the charges. The fact that judges rarely ask questions about the charges or dismiss them at the first appearance no matter how much (or how little) evidence there is speaks to how much judges defer to prosecutors. Judges mostly act as law enforcement.

2. CASE ENDS OR CONTINUES

CASE ENDS

A case can end at the arraignment in two different ways. The (1) first is when the prosecutor moves to dismiss (throw out) the case (which must be approved by the judge). The prosecutor has the power throughout the entire case to move to dismiss any or all charges. The (2) second is when the person charged either (a) pleads guilty to the top charge (charge that comes with the most punishment) and the judge imposes the sentence, or (b) the prosecutor offers them the opportunity to plead to a lower charge. This is also known as a plea bargain, which allows the defendant to plead guilty to a lesser charge in exchange for giving up their right to trial.

Over 90 percent of cases are resolved by plea bargains. The promise of a lesser sentence or a lesser charge is used by the prosecution to entice the person being prosecuted to plead guilty, even if they aren’t.

In a plea bargain, the parties “agree” to resolve the case instead of going to trial. The person accused has to publicly declare that they accept responsibility (admit guilt) for the lesser offense, and they have to accept the corresponding sentence. Only the prosecutor can undercut their own charging decisions and offer a plea bargain. Even though the plea marks the end of the case, potential plea bargains shape how the prosecutor and defense think about the case from the beginning. We’ll get into this more in the plea bargain/negotiation section.

Even if the prosecution does not offer a plea bargain, at any point during the criminal case proceedings, including at arraignment, the accused person can plead guilty to the full charges brought against them.

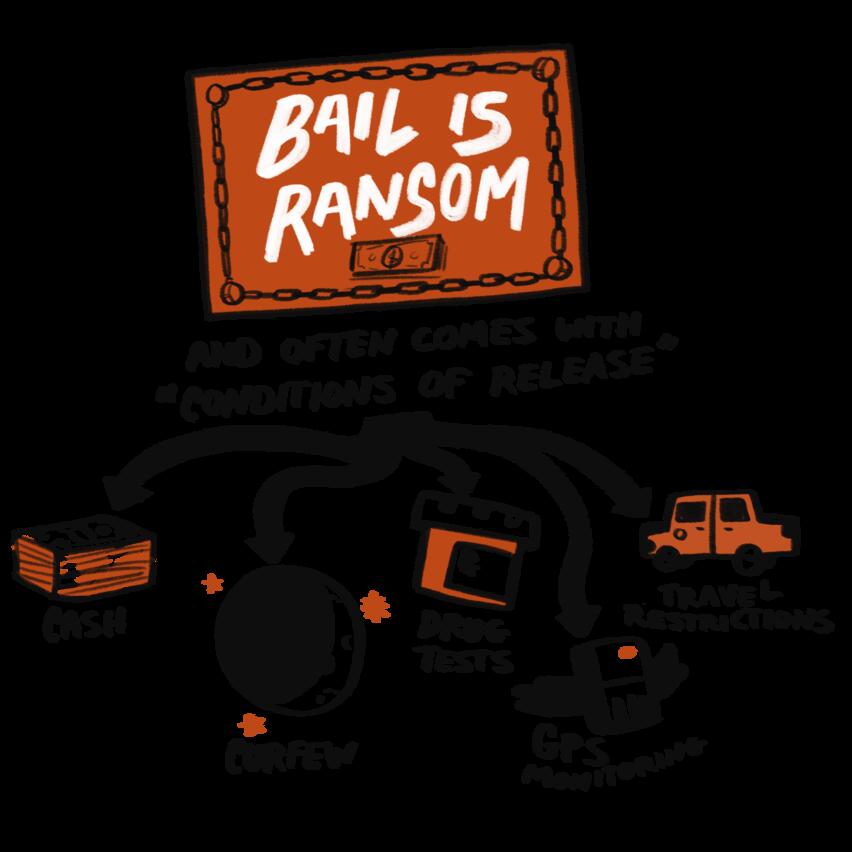

CASE CONTINUES - CONDITIONS OF RELEASE

If a case does not end at the arraignment stage, the judge sets conditions of release, also known as bail, that will last for as long as the case continues, which can be months or even years. The condition that people are usually most familiar with is having to pay money—which is why many people use the term “bail” to specifically refer to money bail—but really “bail” refers to any kind of condition of release. In some places these conditions are decided before the arraignment. Remember that every state and jurisdiction does things a little differently so it's important to find out the details about your particular place!

Bail is the process of securing release for someone who is charged with a crime while they await trial. Conditions of bail or release may be imposed, such as an order to not contact someone, avoid a location, not get re-arrested, wear a GPS monitor (also known as an electronic shackle), take weekly drug tests, or not leave the state. Instead of setting bail or just releasing the accused person during the pretrial period, in some jurisdictions and often depending on the charge, the judge can also decide to send them to jail without the option for release. This is often called preventive detention.

Although bail hearings look different from place to place, typically, what happens is that the prosecutor asks the judge to either (1) send the person accused of a crime to jail until their trial because they pose a “risk to the community” or there is a risk they will not come back to court, (2) set money bail (require them to pay a certain amount of money to be released), or impose other conditions. The defense attorney makes an argument for why their client should be released without conditions during the pretrial period, and if money bail is set, why it should be lower. The judge makes a decision based on the information provided by both sides. Research from New York City shows that the single most influential factor in determining a judge’s bail decision is the prosecutor’s bail request.

In some states, the stated legal purpose of bail (whether money bail or supervision requirements) is supposed to be about ensuring someone comes back to their court dates, in other states their purpose is to both ensure an accused person returns to court AND to protect “public safety.”

Illusion:

The U.S. Constitution requires that money bail be set at a “reasonable” amount. This means you should be able to afford your money bail.

Reality:

Prosecutors request and judges set money bails at such high amounts that many people are unable to afford their bail and instead languish in jail for weeks, months, or years waiting for trial.

Take the case of Lavette, who was arrested in Chicago and unable to pay her bail:

As she describes it in this video, “I was incarcerated for 14 months because I could not afford my bond which was $25,000…When I realized that I wasn't going to be able to go home and afford the bond that they had set, I was very devastated because the first thing I could think about was my kids, I had never been away from them. Before I was arrested, I had a contract with several schools, I had owned my own company, I was on the board at the school that my kids attended. I had a normal life until all this took place. When I went to jail I was very alarmed at how the conditions was in the holding cells. Jail is very costly because they do not supply you with any supplies. You have to buy your own soap, you have to pay for everything you use, from t-shirts to underwear to everything. The prices that you would pay on the streets for food was like ten times more in jail. It became a strain on my family just to put money on my books for the expensive phone calls, trying to get in touch with your kids. When you incarcerate the mother, you incarcerate the whole family…If I was released at the time my bond was set, I don't think my kids would have went through the trauma that it caused the entire family.”

Many also know the tragic story of Kalief Browder, a teenager who was caged for three years on Rikers Island in New York, most of which he spent in solitary confinement, awaiting trial:

Although his case was eventually dismissed, Kalief committed suicide not long after his release. Kalief’s death has raised much-deserved attention about the horrors of money bail because his pretrial incarceration was initially due to the fact his family could not afford the $3,000 bail set by the judge.

But the other important reason he was detained was because the department of probation was blocking his release—there was a probation hold. In many places, if you are on probation, which Kalief was, a new arrest will trigger a probation violation and this may then prevent you from being released during the pretrial period.

Money bail is not the only bail condition used, however. As awareness about the dangers of incarceration has grown, especially during the global COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in judges ordering electronic shackling, home detention, or other supervision conditions during the pretrial period.

Illusion:

Supervision conditions are humane alternatives to incarceration, allowing the accused person to go home instead of being in jail.

Reality:

These surveillance and supervision conditions are really just another form of incarceration and create their own kinds of harm and unfreedom.

Take it from someone currently on pretrial electronic monitoring:

A Cook County judge put Chicagoan Mohawk Johnson on house arrest and GPS monitoring after Mr. Johnson was arrested at a protest during the summer 2020 uprisings.

He regularly posts on his social media the realities of pretrial house arrest and monitoring. He can’t leave his house; he can’t work because no employer is willing to hire him while he is being monitored. The device and software used to track his movements makes mistakes: it generates false violation reports, reporting he has left his house even when he is home or when he had prior approval to go grocery shopping.

Because of how long court cases can drag out, as we will get into in the court appearances section, especially during the pandemic, it's likely Mr. Johnson could be in home detention for years before the case resolves.

Although heavily influenced by the prosecutor’s recommendation, the judge makes the final decision whether to release or detain someone being prosecuted, or whether they will set conditions on the person’s release that, if violated, could result in the judge sending them to jail before the trial. In many places, a judge also uses a risk assessment tool to “predict” an accused person’s probability of showing up for court dates or being arrested for a new charge and then make a detention or release decision. Risk assessment tools have been shown to assign higher risk scores for Black people accused of crimes than white people, even when they are accused of less serious offenses.

The bail decision is one of the most important points of the case. Research shows that whether you are able to fight your case from the outside or are forced to fight it from behind bars dramatically impacts the outcome of a case. It also affects the likelihood of people taking a plea. As we saw with Lavette and Kalief, incarceration for any amount of time ruins lives—people lose jobs, income, housing, education, access to necessary medications, and parental rights; and experience physical, sexual, psychological, and gender-based violence while incarcerated pretrial. ICE is often stationed in jails and, if they find someone who is undocumented, can start deportation proceedings against them.

Pretrial incarceration can also be a death sentence, as it was for Sandra Bland:

In 2015, Sandra Bland was pulled over by a state trooper for a minor traffic offense and then was violently arrested for allegedly assaulting the police officer.

The judge set $5,000 cash bail (refundable if paid to the court, or Bland could have paid a commercial bail bondsman a $500 nonrefundable fee to post her bond), neither of which Bland could not afford. Bland was not alone 63% of people in the US don't have enough savings to cover a $500 emergency.

Three days after her arrest, Bland was found dead in her cell.

Being on supervision and surveillance pretrial also has devastating consequences, as it has with Mohawk Johnson. It is no surprise that people will agree to terrible plea deals to avoid jail or to be released from jail or monitoring. In fact, data from Brooklyn and Philadelphia shows that people are nine times more likely to plead guilty to a misdemeanor if they are jailed pretrial.

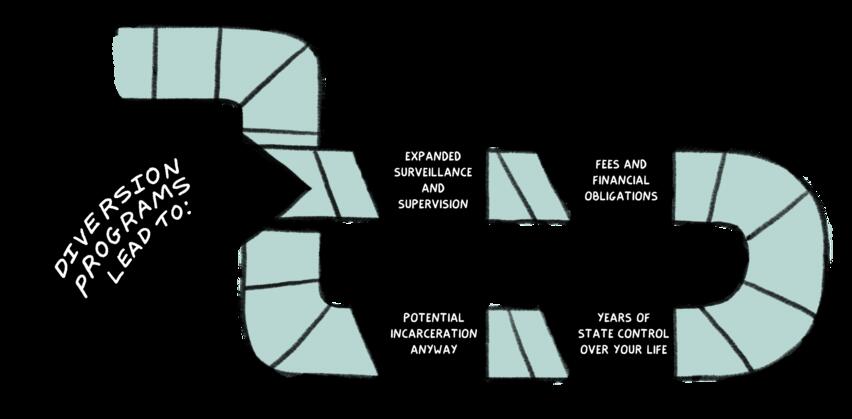

What about diversion or treatment courts?

For cases that continue at the arraignment stage, prosecutors and judges can decide to prosecute the case differently by funneling the case into a problem-solving court (sometimes referred to as a treatment court, speciality court, or status court) or into a diversion program. Whether a case is eligible for these different modes of prosecution depends on the charge, the jurisdiction, and the discretion of the prosecuting office and/or judge.

What makes these modes of prosecution different is that the person being prosecuted enters into, and must successfully complete, some kind of program or requirements (examples can include anger management classes, mental health or drug “treatment,” restorative justice circles, community service, counseling, and payment of fines or restitution) to avoid or reduce a conviction or incarceration.

While these programs—whether mandated by prosecutors or judges—often seem like deals or bargains or alternatives to punishment, they actually expand surveillance and supervision, come with fees and other financial obligations, extend the state’s control over people’s lives for years, and can sometimes be a trap that leads to incarceration. Inpatient programs can especially feel like prison. But, these programs can be tempting because if you can navigate all the requirements, you can often avoid a criminal record or prison time.

There are many reasons why people are not able to complete program requirements and are then rerouted back to prosecution, conviction, and/or incarceration. Here is one example:

In 2011, as reported in The New York Times, Marcy Willis, a single mom in Atlanta, was charged with felony theft after she rented a car for an acquaintance in exchange for cash, and the acquaintance disappeared with the car for four months. Ms. Willis was offered a diversion program by the prosecutor that required her to take 12 weeks of classes, perform 24 hours of community service and stay out of trouble in order for her case to be dismissed and her arrest expunged.

While Ms. Willis fulfilled those requirements, she was unable to pay all but $240 of court fees related to the program. Subsequently, she was sent back to the court for prosecution. During this time she also lost her job and apartment.

Key takeaways

- The bail decision is so important because whether someone is free, jailed, or under some form of supervision during the pretrial period can dramatically impact their ability to fight their case, their decision to take a guilty plea, not to mention their housing, employment, parental rights, and more.

- Supervision, whether in the form of home detention, a GPS ankle shackle, check-ins with a social worker, etc., and whether as a condition of release (i.e. bail) during the pretrial period or as a form of prosecution (i.e. diversion program), is really just another form of incarceration that expands the reach and scope of the criminal punishment system, and creates other kinds of harm and unfreedom.

- Arraignments and bail hearings are key moments in participatory defense campaigns - reach out to community to come to court to show the person charged and the court that the community does not support prosecution, and has many other ideas about how to prevent, interrupt and heal from the harm involved. More on participatory defense here.

- You can fight back against the expansion of diversion programs and problem-creating courts and for the pro-health interventions that do keep people safe. Check out this resource for more information, analysis, and talking points.