Community Interventions to Shift Power Inside Criminal Court

Organizers, community members, people being prosecuted and their loved ones developed these interventions. They include: cop watching, court watching, bail outs and community bail funds, participatory defense campaigns and hubs, and jury nullification.

Criminal court is intentionally designed to be a disempowering, individualizing, anti-democratic space. One person–usually a poor person of color–stands alone in court, separated from their loved ones and neighbors; meanwhile, the government fails to provide the communities that those people are a part of with the resources that they need to stay safe. In spite of this, every day the people most affected by criminalization and their allies participate in the system through bottom-up interventions that shift power and influence case outcomes. If you have ever participated in or witnessed community members filming the police, posting bail for a stranger, or packing courtrooms in support of the person being prosecuted, you’ve seen these interventions in action.

These kinds of organizing interventions are not PIC abolition in and of themselves, but they are abolitionist in that they provide opportunities to shift power, to build power, and to prevent or free people from incarceration or other forms of carceral control. As Mariame Kaba writes about participatory defense campaigns, “Some might suggest that it is a mistake to focus on freeing individuals when all prisons need to be dismantled. The problem with this argument is that it tends to render the people currently in prison as invisible, and thus disposable, while we are organizing towards an abolitionist future. In fact, organizing popular support for prisoner releases is necessary work for abolition. Opportunities to free people from prison through popular support, without throwing other prisoners under the bus, should be seized.”

Cop Watching

Cop watching is filming the police - or other law enforcement agents, such as ICE - as they interact with people in public. Cop watching can happen spontaneously by a passerby witnessing someone being harassed by the police. It can also be an organized effort - often called patrols - where people come together intentionally for the purpose of copwatching in a group.

The power of copwatching exists in the potential deterrence of police violence (whether the everyday or the spectacular) in the moment - cops often behave differently if they know they are being watched. Importantly, as law professor Jocelyn Simonson writes, “copwatchers’ control over their own actions, data, and participation turns the tables on the traditional control that state officials possess to dictate the terms of public participation, and, by extension, to define the public to whom the system is accountable.” When you copwatch, especially with others, you shift power away from the police.

Examples:

- Since 2008, the Justice Committee in NYC has been conducting copwatching patrols, which they describe as “an act of self defense rooted in love and solidarity.”

- Berkeley Copwatch has been copwatching for thirty years, filming the police & serving as a hub for reports of police violence. Recently, they partnered with WITNESS to create a People’s Database to gather and archive videos of police behavior.

Court Watching

Court watching is when people from the public sit in courtrooms to observe what happens: bail hearings, arraignments, pleas, trials, and just the everyday court appearances that constitute the delay and violence of criminal court. Sometimes this looks like formal monitoring programs, composed of volunteers or organizational staff who sit in courtrooms regularly to document what happens and report to the public the results of their observations. And sometimes this looks like family, friends, and supporters filling courtrooms (often called “packing the court”) in support of a loved one who is being prosecuted.

Like copwatchers, court watchers serve as self-appointed watch dogs whose presence can influence the outcome of a specific person’s court case. The prosecutor can no longer purport to be the only or primary representative of “the people.” Court watchers also can share the observations they collect with the public to ensure accountability and raise awareness about the violence within the seemingly mundane and bureaucratic criminal court procedures, processes, and discretionary decisions of judges and prosecutors. When the observing, documenting, and reporting is connected to a larger social movement or organizing campaign, court watching can build power.

Examples:

- Some courtwatching projects, like Court Watch NYC and the court watching initiative of the Coalition to End Money Bond in Chicago, have used courtwatching to expose the carceral practices and decisions made by powerful court actors like prosecutors and judges.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, Baltimore Courtwatch and other groups have been able to use virtual courtwatching as a part of long-term abolitionist organizing in collaboration with other local groups. Baltimore Courtwatch has tweeted the results of every single bail review hearing in Baltimore city circuit court since April 2020.

Bail Outs and Community Bail Funds

Whether a one time mass bail out, or a revolving bail fund, this tactic involves the pooling of money to post bail and free individuals from pretrial incarceration. Most often the people donating funds and posting the bail are not connected to the person being bailed out, but are doing it out of communal interest in pretrial freedom.

When a prosecutor requests and/or a judge sets money bail, they do so purportedly in the name of the “community” or “public safety.” In posting bail for strangers, bail funds refuse to let the prosecutors or judges speak for the community and they assert a different version of safety outside of the criminal punishment system.

Examples:

- The Chicago Community Bond Fund, which is part of the National Bail Fund Network - a network of over 90 community-based pretrial and immigration bail and bonds funds, works to get people free through paying bail while also organizing statewide to end the pretrial detention system in Illinois. In 2021, as part of the Coalition to End Money Bond and Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice, their work led to the successful passage of legislation that ends the use of money bond in Illinois.

- As part of the annual National Bail Out collective’s Black Mama’s Bail Out and connected to the campaign to close the jail in Atlanta, in 2019 Southerners on New Ground (SONG) bailed out dozens of Black mothers and caregivers incarcerated in the city jail.

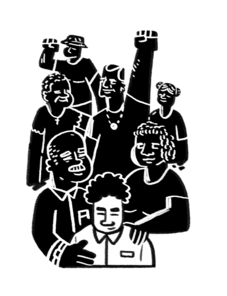

Participatory Defense Hubs / Defense campaigns

Participatory defense hubs and defense campaigns are when people facing charges are joined by family members, friends, supporters, and advocates to deploy a variety of tactics to impact the outcome of individual cases and ultimately transform the power dynamics in the courtroom. These tactics can include creating mitigation packets or videos, conducting investigations, packing courtrooms with supporters, fundraising, raising awareness, pressuring decision makers, and attending to the needs of the person facing charges and their family.

Participatory defense hubs are often ongoing organizing formations that typically bring together the supporters of several different individuals facing charges whereas defense campaigns, although connected to larger social movements, are for individual cases.

Participatory defense hubs and defense campaigns show the prosecutor and the judge that the people facing charges are not doing so alone - their freedom from prosecution and incarceration is supported by a network of individuals, and often the larger public. In many cases, this has led to acquitals or more lenient sentences.

Examples:

- The Nashville Participatory Defense Hub, which is part of the National Participatory Defense Network and coordinated by Free Hearts, holds weekly meetings with people fighting cases and their families. Participatory defense hubs often use the language of “time saved” versus “time served,” in order to show how their collective organizing and support made an impact in lessening the number of years someone might have spent in a cage. Since 2017, the Nashville hub has saved over 967 years of incarceration.

- The #FreeBresha Defense Campaign shined international and national attention on the case of Bresha Meadow - a fourteen year old who shot her abusive father in self-defense. Utilizing actions like creating a petition to drop the charges, organizing mass-letter writing to the prosecution, raising money for legal fees, organizing rallies and vigils, organizing court support, uplifting her story and the story of other criminalized survivors on social media and mainstream media, and more, the defense campaign was successful in achieving a reduced sentence for Bresha and generating awareness about the criminalization of survival more broadly. The #FreeBresha campaign is one of many survivor defense campaigns connected with Survived and Punished.

Jury Nullification

Juries are among the primary ways that the community participates in the punishment system, and one of the most powerful ways to do that is to say no to a prosecution or a punishment.

Jury nullification is the power that jurors have to find a person facing charges not guilty, even if there is evidence to technically convict them of a crime. As a juror - whether on a grand jury or trial jury - you have the power NOT to indict or convict someone, for whatever reason, including if you think the law itself is unfair or unfairly applied.

It is difficult to find examples of organized efforts of jury nullification. This is because while it is perfectly legal for a juror to nullify for any reason, courts have decided they are not required to inform jurors of their right to nullify. They can remove jurors for openly considering their option to nullify. People have also been arrested and prosecuted for distributing pamphlets about jury nullification in front of courthouses. Additionally, it is a radical and difficult move for a lay person, in the face of a judge, a prosecutor, court officers, other jurors, and general societal conditioning, to vote no in the face of obvious probable cause. Even asking probing questions can feel difficult and is often discouraged.

A juror who says “I am nullifying because I think the system is unfair” risks getting removed from the jury. Rather, a juror who wants to nullify will have to do so covertly. If they want to convince other people to do the same, they will have to build trust and educate others. They might have to convince their peers to acquit on the basis of evidence, even though they believe that the real reason to acquit is because the system is corrupt.

When jurors do decide to nullify, they are sending a message to prosecutors, police, and lawmakers that the status quo operations of the criminal punishment system are unacceptable. For abolitionists, this means that saying “not guilty” in one case can become a larger statement that the entire system is devoid of justice.

Examples:

- Paul Butler has argued that jurors in Washington, D.C. should (and have) found people not guilty of drug-related crimes out of a larger belief in the racial injustice of the system, and that jurors around the country may nullify cases with police abuse in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives.

- It can be hard to identify specific cases where a jury nullified, as jurors do not have to discuss their secret deliberations. In the UK in May 2021, a trial jury acquitted several activists with a climate justice organization, Extinction Rebellion, who were charged with causing almost $30,000 worth of damage to Shell’s headquarters in London. The accused activists admitted they had done the thing they were accused of, however the jury decided to nullify, presumably because they believed the actions of the activists were morally right.

Learn More

- What is Community Justice? By Jocelyn Simonson

- We’re Watching: A Guide to Recording the Police & ICE by the Justice Committee and Center for Urban Pedagogy

- So You Want To CourtWatch? By Community Justice Exchange

- Democratizing Criminal Justice Through Contestation and Resistance by Jocelyn Simonson

- Organizing Toward a New Vision of Community Justice by Raj Jayadev and Pilar Weiss

- Free Us All by Mariame Kaba

- #SurvivedAndPunished: Survivor Defense as Abolitionist Practice Toolkit by Survived and Punished

- Participatory Defense: Re-Defining Defense and Using People Power as a Tool for Liberation by the #FreeOusman Defense Team