Defunding Courts

Over the past two years and the past two decades, abolitionist organizers have waged campaigns to divest from institutions that kill, harm, cage and control our communities, and invest in housing, health care, income support, employment, and community-based safety strategies that will produce genuine and sustainable safety for all.

And, they haven’t stopped there. They have also extended defund demands to courts and prosecutors, who are also critical players in the prison industrial complex. Professor Brendan Roediger refers to courts as “an expressive component of police bureaucracy,” while scholars Amanda Woog and Matthew Clair name courts as sites of state violence, coercion and control. Like police, prosecutors and criminal courts are also promoted as essential to public safety. Yet much of what criminal courts adjudicate bears no relationship to harms people experience. For example, in 2022, there were almost 13 million misdemeanor charges that forced thousands of people into the criminal justice system each year. More than a quarter of all cases filed in criminal courts are motor vehicle, drug and broken windows offenses, so called “low-level” crimes that police and prosecutors pursued aggressively in cities particularly in the 1990s.

And when real harm occurs, criminal courts’ default solution is prison or supervision. Those measures do little to prevent, interrupt, or heal harm, or transform the conditions that produce harm. Instead they make things worse. With little to show for themselves but social control, criminal courts play a toxic role in our society. Recognizing this reality, organizers are extending calls to #DefundPolice to #DefundCourts by shrinking court and prosecutors’ offices’ budgets.

Prosecutors Fueled Mass Incarceration

At any given moment, the number of people accused of crimes and the number of criminal cases pending in a courthouse depend on the choices and actions of police and prosecutors, namely the number of arrests they make and the number of cases they file.

Professor John Pfaff has shown that increases in the number of prosecutors and case filings played a significant role in fueling growth in prison populations during the historic incarceration boom at the turn of the twentieth century. As reported crime rates rose sharply between the 1970s and the 1990s, prosecutors’ offices hired approximately 3,000 more prosecutors nationally, representing a 17 percent increase in staffing levels. As reported crime fell between 1990 and 2007 by 35 percent another 10,000 prosecutors were hired, swelling their ranks to 30,000. As the number of reported crimes decreased, so did arrests, but the number of prosecutors, and the resources at their disposal, remained the same. (Of course, crime statistics are notoriously unreliable, but politicians, police departments and prosecutors have used them selectively to increase their power and size).

With increased capacity, prosecutors’ offices charged more felonies per arrest. Pfaff shows that this increase in felony filings resulted in increased numbers of people sentenced to prison and fueled mass incarceration. Of course, it is not just prosecutors who are responsible for the astronomical number of people who are arrested, prosecuted, incarcerated, supervised and killed by the carceral state. Legislators, courts, police officers, judges in particular were and remain deeply complicit. The Supreme Court gave police departments more legal authority to stop, detain and arrest more people, with less evidence and with greater force. It also shielded prosecutors from accountability. Lower courts meanwhile routinely defer to police officers’ testimony, ignore lies and elevate them as experts. Federal and state legislators for their part gave police departments bigger budgets to buy more lethal equipment and more officers. And they also passed tough on crime laws that made it easier to arrest and incarcerate, for longer periods of time, which only enhanced the power of police, prosecutors and criminal courts. Meanwhile, legislators and politicians refused to adequately fund their constituents' needs for welfare, public health, childcare, schools, and housing.

But, as we show in Criminal Court 101, prosecutors are a powerful actor in the machinery of oppression. Prosecutors also make for good targets. And while there has been great attention and energy invested in electing so-called “progressive prosecutors,” a strategy which we critique here, if we want to reduce the harms of criminalization and incarceration and increase the resources available to prevent, interrupt and heal from harm, we can start by reducing the number of prosecutors and their budgets.

#DefundCopsCourtsandCages

As we discuss here, many of the common reforms aimed at criminal courts preserve or expand criminalization, whether intentionally or inadvertently. And unsurprisingly, the country continues to arrest, supervise and incarcerate millions of people. Rather than trying to make criminal courts more fair, more transparent, more attentive to trauma, we argue it’s high time to move beyond criminal courts. By doing so, our hope is to avoid the pitfalls of cooptation and to advance strategies that address the root of the problem: criminalization itself. We uplift the work of organizers who are trying to shrink criminal courts’ power by cutting their budgets. Their work to defund courts builds on their ongoing campaigns to defund police.

The Black Nashville Assembly’s campaign to “Defund Cops, Courts & Cages” is one example of such an approach, inspired by organizing with people caught up in the criminal punishment system. As Erica Perry of the Black Nashville Assembly puts it, “Because we were led by people who are directly impacted, we were forced to look at what it looks like to be taken into custody by police, be put in a cage because you can’t afford bail, and then put in front of court for an arraignment in front of an anti-Black prosecutor and judge. We were able to organize people around their rage around their experiences with the police, inside the jail, and inside the courts.”

The campaign specifically targets specialized courts such as drug court, veterans’ court, and domestic violence court. Perry describes these programs as “coopting our language around wanting people to have access to services instead of incarceration by saying ‘we want people to have services so we want to arrest people and force them to access social services they have to pay for in order not to be convicted.’” Black Nashville Assembly developed a survey it distributed in the community asking people where they wanted to take money from in the city budget, and where they wanted to invest it - many people wanted to take funding from police, courts and jails and invest it in other resources like community-led harm prevention and transformative justice. BNA will now use the information gathered from the survey in prosecutor and judicial elections to question candidates on whether they are willing to meet those demands, and as a part of their invest/divest campaign to shrink the size and power of local courts and the DA's office.

Seattle’s Solidarity Budget offers another example of a comprehensive approach to defund campaigns. Angélica Cházaro grounds this approach in a 2016 fight to stop construction of a youth jail, which in turn required reduction of juvenile prosecutions: “if we are not going to have youth incarceration, we also shouldn’t have youth adjudication—we can use fights to close or stop jails to push folks toward the inevitable conclusion that we don’t need any parts of this system.” As Cházaro underscores, ending youth incarceration and all incarceration means ending prosecution too.

In 2020, the Seattle Solidarity Budget coalition initially called for defunding the Seattle Police Department by 50 percent, and worked with the local public defenders to put forth an ordinance in the Seattle Municipal Code to curb the criminalization of behavior related to unmet mental health needs, poverty, and drug use. Cházaro points out that this demand met the greatest resistance: Seattle politicians and business groups seemed less opposed to reducing resources to police than curbing misdemeanor prosecutions and defunding municipal courts.

Nonetheless, in its second year, the Seattle Solidarity Budget broadened its demands, and also called for a 50 percent cut to funding for the criminal divisions of the City Attorney’s office and the Seattle Municipal Court. The City Attorney’s Office prosecutes misdemeanors in municipal court where poor people are targeted, hidden, and dehumanized. In addition, the Solidarity Budget campaign demanded the decriminalization of misdemeanor offenses. In their budget proposal, the campaign rejected the municipal court’s justification for increased funding and power based on offering alternatives to incarceration for misdemeanor offenses. “Courts and prosecutors are not social service agencies, and should not be the gateway to housing and treatment. Just as responses to mental health crises belong in community hands . . . courts and prosecutors should not be funded to provide the basic support and programming people need.”

The Seattle Solidarity budget includes demands to use the resources currently funneled into municipal court to create workgroups of community members and stakeholders to develop alternatives to misdemeanor prosecutions, including misdemeanor domestic violence cases, which currently account for a third of municipal court costs, and to develop a 5-year plan to end municipal court prosecutions in Seattle. These efforts include developing a just transition for court workers, many of whom, including probation and parole workers, are Black, Indigenous or people of color in union jobs. Organizers have begun to make inroads with unions representing court workers by asking “what is it you like about your job? Wouldn’t it be great to be able to do the things you want to do for your community in ways that are not based on violence or the threat of violence?”

Deploying Strategies to Defund Courts in Your Community

At the heart of organizing that aims to defund carceral institutions community efforts to reimagine public safety and public spending. In Seattle, Nashville and other cities, organizers have developed their own proposal for budgets that would create greater safety for all.

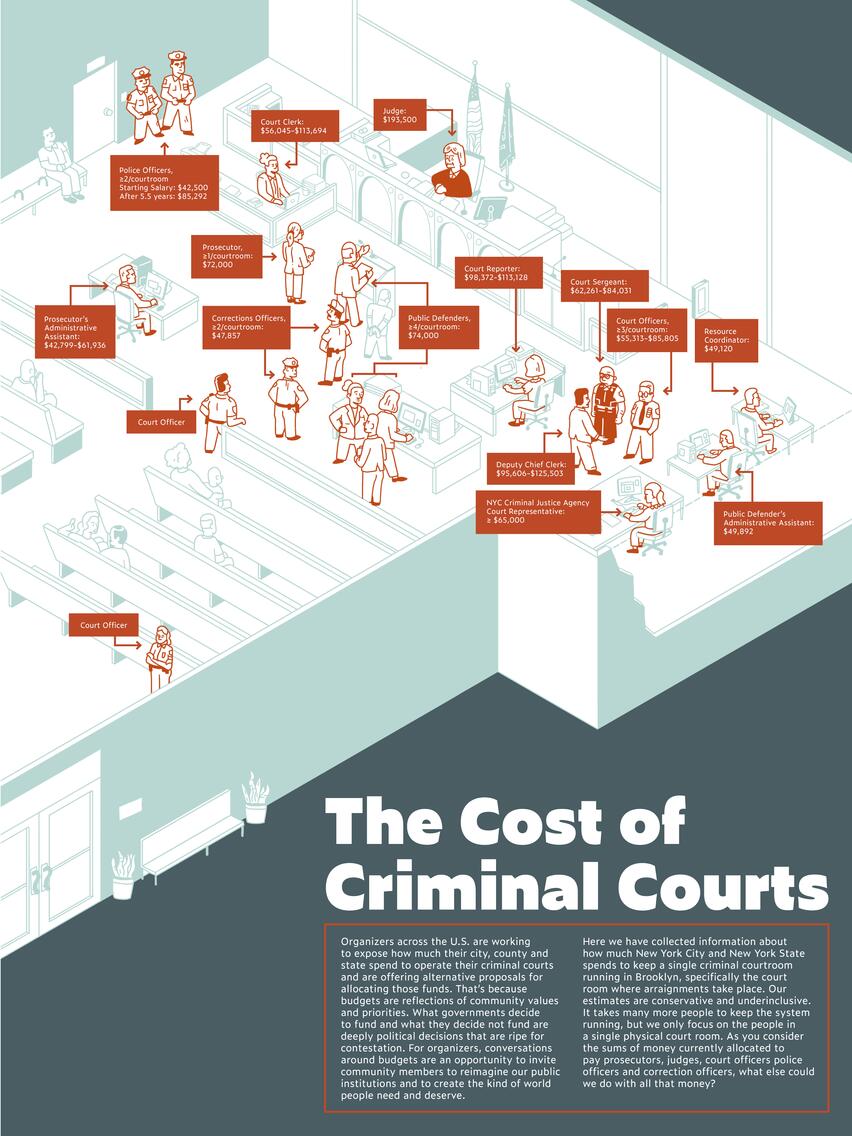

Budgets are reflections of community values and priorities. What governments decide to fund and what they decide not fund are deeply political decisions that are ripe for contestation. For organizers, conversations around budgets are an opportunity to invite community members to reimagine our public institutions and to create the kind of world people need and deserve.

Organizers are working to expose how much their city, county and state spend to operate their criminal courts and offering alternative proposals for allocating those funds. In Seattle, organizers have trained their eyes on municipal court. They have started by working to eliminate the kinds of criminal prosecutions many people agree are harmful and wasteful. But critically, they have not just focused on these types of offenses. For example, they have also won funding for a working group that can help make the case to the public and city council that even instances of domestic violence are best addressed outside of criminal court. In order to accomplish this, organizers are not only identifying how to divest, but also how to invest in community care to truly address the sources of harm.

Social Movement Support Lab has already developed a sophisticated tool to uncover how much your jurisdiction spends on policing, courts, and prisons. You can supplement this data with local information about how much criminal courts cost in your community. For example, check out the cost breakdown for one courtroom in Brooklyn, NY where arraignments take place. Our estimates are modest. We only include the lowest salary ranges and do not include other forms of benefits and payments employees may receive. We only count the people physically inside the courtroom. But it takes many more police officers, prosecutors, court officers, lawyers to bring a case from arrest to arraignment, but here is a snapshot.

As you consider a #DefundCopsCourtsandCages or #DefundDA campaign in your community, here are some questions to consider:

- How could the money currently allocated to pay prosecutors, judges, court officers, police officers and correctional officers be better spent? What would be better ways to put our collective energy and resources to use?

- As we push to shrink the size, scope and power of courts and its carceral agencies, how can we protect individuals currently navigating courts and prosecutions? What kind of backlash can we anticipate and how can we defend against it?

- How can we build alliances across movements to demand budgets that deliver comprehensive and inclusive prosperity and safety for us all?

Thanks to Octavia Ewart, Regina Yu and Professor Jocelyn Simonson for research support on this resource.