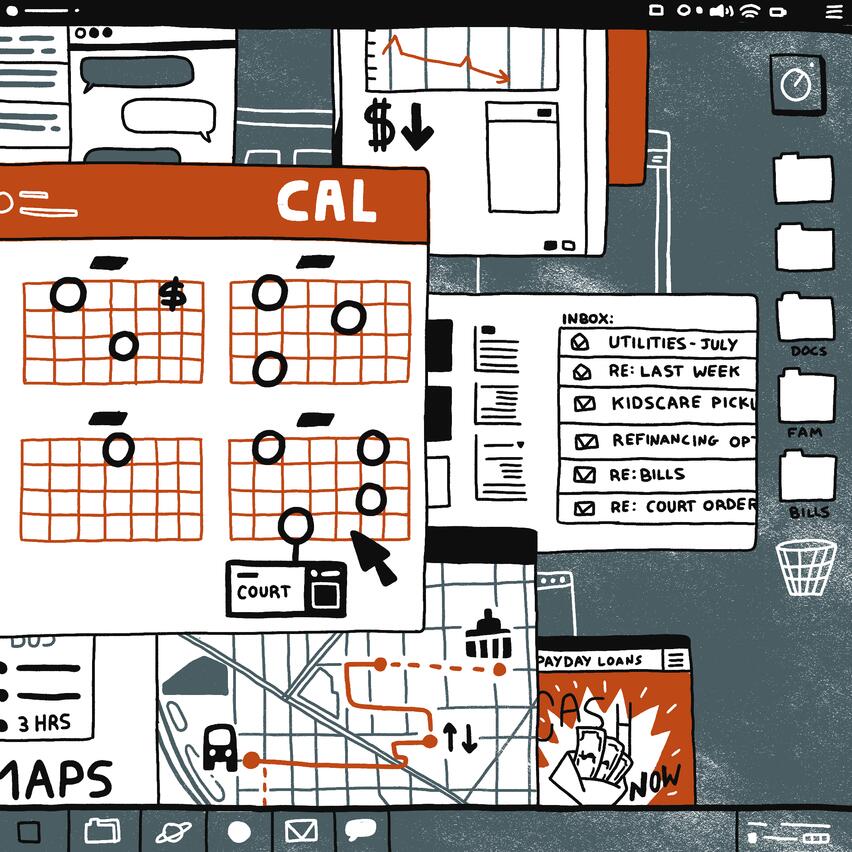

Court Appearances

If a judge or grand jury finds probable cause to continue prosecution, the next step is regular court appearances until the case goes to trial, is dismissed, or resolved through a plea bargain.

These court appearances serve a range of different purposes: lawyers file motions and the prosecutor and defense update the court about their investigations and their preparations for trial or plea negotiations. These court appearances are supposed to help each side prepare for trial and for the judge to rule on important matters regarding the kind of evidence that can be introduced at trial.

Illusion:

If probable cause is found to continue prosecution, while there may be a few court appearances in between, a trial will begin almost immediately, like on Law and Order.

Reality:

This time period for court appearances can actually be lengthy, depending on the case. In some cases, court appearances can stretch on for years before a trial even starts, if it ever happens at all. Court congestion (many people being prosecuted at the same time) can prevent cases from being resolved.

The high stakes of the cases means that the defense may want to delay a prison sentence, especially if the accused person is free pretrial. A judge or court administrator can also delay a case by claiming that the courts are too busy to hold a trial, or that a co-defendant's case must be tried first. Sometimes the time period can be lengthy because the case is complex: each side may have witnesses and experts to prepare. Other times, the reason there are many court appearances is because the prosecutor’s witnesses do not want to cooperate, but the prosecutor does not want to admit defeat.

Take the case of Carlos Montero, who spent seven years on Rikers Island before taking a plea to time served:

Neither the prosecution, courts, or defense would take ownership over the delay, instead pointing fingers at each other. At the time he was on Rikers in 2015, at least 400 other people incarcerated there had been waiting at least two years for their cases to go to trial.

While time limits for prosecutions can be extended by both the prosecution and the defense, it is typically far more advantageous (and biased towards) the prosecutor who does not want to, nor do they have staffing to, bring every case to trial. While there are technically some limitations on how long the prosecutor can drag out the case (i.e. speedy trial laws), those time periods have a lot of loopholes, are vague, or are not enforced.

Prosecutors can also find ways to get around the rules because of the high number of criminal cases. For example, prosecutors can declare themselves ready for trial, and thus avoid running out the clock, when there are not enough courtrooms or judges to actually start the trial. That means that prosecutors can take their time before being forced to resolve the case or take it to trial. They control the time.

Look what was uncovered about the Bronx District Attorney office in 2018:

In 2018, an exposé of internal training documents from the District Attorney office in the Bronx, NY revealed that prosecutors were being trained in courtroom techniques with the explicit goal of stretching out cases. This prosecutorial practice of manipulating the system to delay cases in order to secure guilty pleas is not unique to the Bronx.

Regardless of why the delays happen, for people who are incarcerated pretrial the many court dates and length of a case can be tortuous. The longer you spend in jail, the more likely you are to accept a guilty plea even if you are not guilty. However, even for people who are free pretrial, attending endless court dates comes with its own set of challenges—having to take entire days off work or figure out childcare just to sit in a courtroom, waiting to see a judge, and nothing happening with your case. For those on pretrial supervision, the consequences for health, employment, family, and more are prolonged. The accused pays the penalty for the delays, either as time spent incarcerated pretrial or time spent coming back and forth to court for court appearances, unable to get on with the rest of their life.

Illusion:

The defense has access to all the evidence the prosecutor has gathered before the trial begins.

Reality:

Unfortunately, no. Although there are rules that require the prosecutor to turn over evidence, only they know what evidence they have. The defense attorney doesn’t get to go through the prosecutor’s files, and neither can the judge. It is the prosecutor who decides what evidence to give the defense.

Although prosecutors are under an obligation to turn over evidence that is favorable to the defense, there are not strong means of forcing prosecutors to do so. This leaves many people making decisions in the dark.

Additionally, in general prosecutor offices can access evidence much more easily than the defense because prosecutors are government officials. They have more power, clout, and authority than the defense. Prosecutors also have more resources, such as police officers, to conduct their investigations. And, businesses are more likely to turn evidence over to the government than to an individual accused of a crime.

This is what almost led New Yorker Aaron Cedres to take a plea bargain, even though he was certain security footage of the incident would exonerate him:

The Marshall Project tells the story of his wait for evidence (also known as discovery) to be turned over: “Cedres and his lawyer, Kristin Bruan, said that at first he refused the plea, but as the months wore on, he began to consider it. Pending felony charges meant that he lost his job, then his apartment and car. His girlfriend moved into her mother’s house with the couple’s infant daughter, and Cedres was homeless. Bruan wondered if Cedres accurately remembered the chaotic event, or if his single punch was enough to make him guilty under the law.

Prosecutors in this case turned over police reports indicating that the victim and his girlfriend had found Cedres on Facebook, identified him as a leader of the assault and were willing to testify...Bruan filed a motion for discovery shortly after Cedres was arrested. Under the law, the prosecution had 15 days to hand over the material or explain why it would not. Fifteen days passed with no reply, then 30, Bruan said.

Judges have few available sanctions for prosecutors who do not comply with discovery requests. More than two months after Bruan’s initial request, the prosecutor wrote that the video “does not show anything/is corrupted,” an email shows. Bruan pushed back, and after another five months of wrangling, the videos appeared in her inbox. They showed almost exactly what Cedres said they would: In the mayhem, he threw two punches to free the club owner’s son from a bear hug. A separate fight spilled down the street, where a crowd of people beat the man who was ultimately seriously injured. After a year and a half and 22 court appearances, the charges were dismissed.”

Key takeaways

- During the lengthy period of court appearances, regardless of why they are stretching on so long or who is to blame for the delay, the accused person (whether they are in jail, on supervision, or technically free) remains in limbo, in the clutches of the court system, unable to continue on with their life.

- There are no strong mechanisms to force prosecutors to turn evidence they are obligated to provide over to the defense, meaning that the prosecutor often knows a lot more going into trial, leaving people accused of crimes to make decisions about their case—specifically whether to take a guilty plea—while in the dark.

- Court appearances are key moments in participatory defense campaigns - reach out to community to come to court to show the person charged and the court that the community does not support prosecution, and has many other ideas about how to prevent, interrupt and heal from the harm involved. More on participatory defense here.