Plea Negotiations & Bargain

When we say most cases are resolved by plea bargain, we mean that the person accused of a crime accepts responsibility in open court, rather than going to trial. Sometimes they are pleading guilty to the top charge of the indictment, sometimes they are pleading to a lesser charge because their attorney and prosecutor negotiated a deal. When we say someone took a plea, it does not necessarily mean they got the benefit of a plea bargain.

To reach a plea bargain, the defense and prosecution start negotiations. Those negotiations can start at any point during the prosecution of a case and can be initiated by either side. The idea is that the defense or prosecution want to resolve the case and want to avoid trial.

As a quick recap, a plea bargain is when the prosecutor allows someone to plead to a charge with a lower punishment than the maximum charge. The guilty plea is in exchange for going to trial. Only prosecutors can offer a plea bargain, and judges have the power to refuse to accept them. Both judges and prosecutors also have the power to dismiss a charge.

Illusion:

Plea bargains are agreements that satisfy the needs of both sides and a plea is something the defense elects to do for their own convenience, or because they are guilty. Indeed, when the person accused pleads guilty they have to tell the judge that they are pleading freely, voluntarily and knowingly. The judge will often ask, “Is there anyone forcing you to plead guilty?” The person accused will have to say “NO,” if they want the judge to accept the plea.

Reality:

Although an accused person has to agree to plead guilty, there are strong pressures to avoid trial, especially if you are incarcerated pretrial.

Remember: prosecutors will always charge the highest possible charge, and will even charge crimes that they know they cannot prove at trial. They do that for leverage in plea negotiations. Given the deference grand jurors and judges give to prosecutors in their charging decisions, prosecutors’ decisions about charges brought as bargaining chips go unchallenged. Prosecutors can virtually guarantee a particular result in a case based on the choice of charge(s) they bring and the kind of plea offer they make. If the top charge is high enough and the plea bargain offer is a substantial enough discount or bargain, then they can create circumstances that all but guarantee a guilty plea. Or, they don’t even have to offer a bargain, if the maximum sentence is long enough to compel the defendant to plead guilty now, in the hopes of receiving less than the maximum.

This compulsion is all the more pronounced when the defendant is taking a plea without the benefit of a plea bargain. Think about it: the accused is giving up their right to trial, without even getting the benefit of a reduced sentence. They are likely doing so because they fear that the sentence after trial will be much longer than the sentence if they take a plea.

Here is one example of why someone might choose to take a plea deal:

Bresha Meadows, a Black teenager who shot and killed her abusive father when she was fourteen, was initially facing a sentence of 25-years-to-life and instead of going to trial, decided to take a plea deal. The terms of the plea deal dropped her aggravated murder charge to involuntary manslaughter and she was sentenced to a year and a day in juvenile detention, with credit for time served, as well as six additional months at a residential mental health facility and two years of probation.

Would a jury have seen Bresha’s desperate act as self-defense and granted her an acquittal? Risking a potential life sentence made the attempt understandably untenable and so instead, like so many, she took the deal.

Illusion:

Only people who are guilty decide to accept a plea bargain.

Reality:

Because so much behavior is criminalized, it is true that a lot of (maybe even most) people who accept plea bargains have violated at least some criminal law. However, why people accept guilty pleas has less to do with actual guilt or innocence, and more to do with the risk of taking the case to trial and losing.

When someone goes to trial, they are tried for the maximum charges the prosecutor selects. If they lose at trial, in most states, it is up to the judge to make the ultimate decision on the sentence. In general, judges impose harsher sentences if a person takes their case to trial. This is called the trial penalty. To avoid the trial penalty and the potentially lengthy sentence at trial, many accused people settle for the plea offer the prosecutor makes.

This is an example of what the trial penalty looks like in practice:

Unlike Bresha (and most people), New Yorker Robert Rose decided to turn down a plea deal that came with a 3-9 year prison sentence and take his chances with a trial, trusting the jury would believe his self defense claims. Unfortunately, they did not and found him guilty, and the judge sentenced him to twenty five years to life, a sentence far harsher than the plea offer he could have agreed to. He ended up serving 24 1/2 years.

This difference between what he could have received by taking the plea offer, versus what the judge sentenced him to after asserting his constitutional right to trial, is what we mean when we talk about the trial penalty.

Illusion:

The prosecution and defense have the same amount of power in plea negotiations.

Reality:

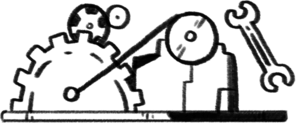

Plea negotiations happen between the prosecutor and the defense and they happen outside of court, and outside of the view of the judge. It’s like a private conversation, but each side does not have the same power. In fact, the power differential between the prosecution and defense in plea negotiations cannot be overstated.

The prosecutor is concerned with increasing their conviction record and public profile, reducing their workload, and sometimes the feelings of the so-called victim or complainant involved in the case. They have a police force and a political apparatus behind them to support their prosecution and very little personal skin in the game. They often do not come from the same community or look like the person they are prosecuting—and even if they do, it doesn’t necessarily change their priorities.

People being prosecuted, on the other hand, have everything to lose: health, family, life, and freedom. Their only power is their willingness to plead or to force the prosecutor to work to bring the case to trial. Their defense lawyer is worried about their client serving a long sentence. They also might be considering the potential stress of trial and the concern that the case might drag on for years as they wait for a trial. The prosecutor also has a lot more leverage—after all, the prosecutor sets the terms of the plea negotiations because they determine the charges, and the maximum permissible sentence in the case. In general, in these negotiations, the prosecutor will want to remain as close to the top charge as possible. The defense will try to bring the charges and sentence down as much as possible.

The prosecutor, as the government, also has a lot more resources than the defense to investigate the case. They also have an entire police department at their disposal for the investigation. Police officers are often their star witnesses at the grand jury, hearings and trial. Legally, prosecutors have the burden at trial to prove that the defendant committed the crime, beyond a reasonable doubt. That means they hold all the evidence. All these factors combine to give the prosecutor most of the power in the plea negotiations—they are in control.

Illusion:

Prosecutors have to abide by certain rules and respect the defendant’s constitutional rights in these negotiations.

Reality:

There are virtually no rules or laws governing how prosecutors and defense attorneys conduct these negotiations. Although a prosecutor cannot legally say they are making decisions based on the race or gender of the person they are prosecuting, there is nothing stopping them from considering that privately.

Furthermore, the prosecutor can use any number of tools to compel an accused person to take the plea deal. For example, a prosecutor can threaten the death penalty or a life sentence to force an accused person to take a plea to a lower charge, rather than to take the case to trial. And when an accused person takes a plea because she is scared that if she does not, she will spend the rest of her life in prison, the law will still treat her decision to plead guilty as voluntary, even if it is anything but.

Plea Bargains in the Form of Diversion or Alternatives to Incarceration

Sometimes, depending on the charge and circumstances, prosecutors will offer that the person being prosecuted enter into a diversion and/or alternative to incarceration (ATI) program as part of their plea bargain. If they complete the program successfully, the charges could be dismissed completely or lowered. Read more about the pitfalls—and power dynamics—with diversion programs, alternatives to incarceration, as well as problem-solving courts here.

Here is one example of when pleading to an ATI program is not an alternative to incarceration at all:

Pat Howard, a mom of five based in Indiana, was charged with felony burglary after climbing through her best friend’s window to retrieve a bottle of her own medication. Felony burglary comes with a minimum of ten years in prison and so, upon advice from her lawyer, Howard decided to take the prosecutor’s plea bargain: plead guilty to a lesser charge that came with five years on house arrest, surveilled by an electronic shackle, and another five years probation.

As detailed in Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law’s book Prison By Any Other Name Howard’s monitoring was not only expensive ($115/week), but it impacted her entire family—allowing caseworkers to inspect their house at any given time, requiring her husband not to drink alcohol or own firearms, preventing Howard from taking her kids to the park or attend their school events, and more. As Howard is quoted as saying, “‘In home’ is a type of incarceration, regardless of the other definitions provided.”

Key takeaways

- The system is designed to give the prosecution all the power in the plea negotiations, ensuring that over 90 percent of cases are resolved through plea bargains.

- People do not risk taking their case to trial because the system is stacked against them so violently that to risk doing so could mean a much longer time in prison.