Trial

A trial occurs when an accused person does not plead guilty, either because they turn down the plea offer made by the prosecutor, or because the prosecutor simply does not make a plea offer at all.

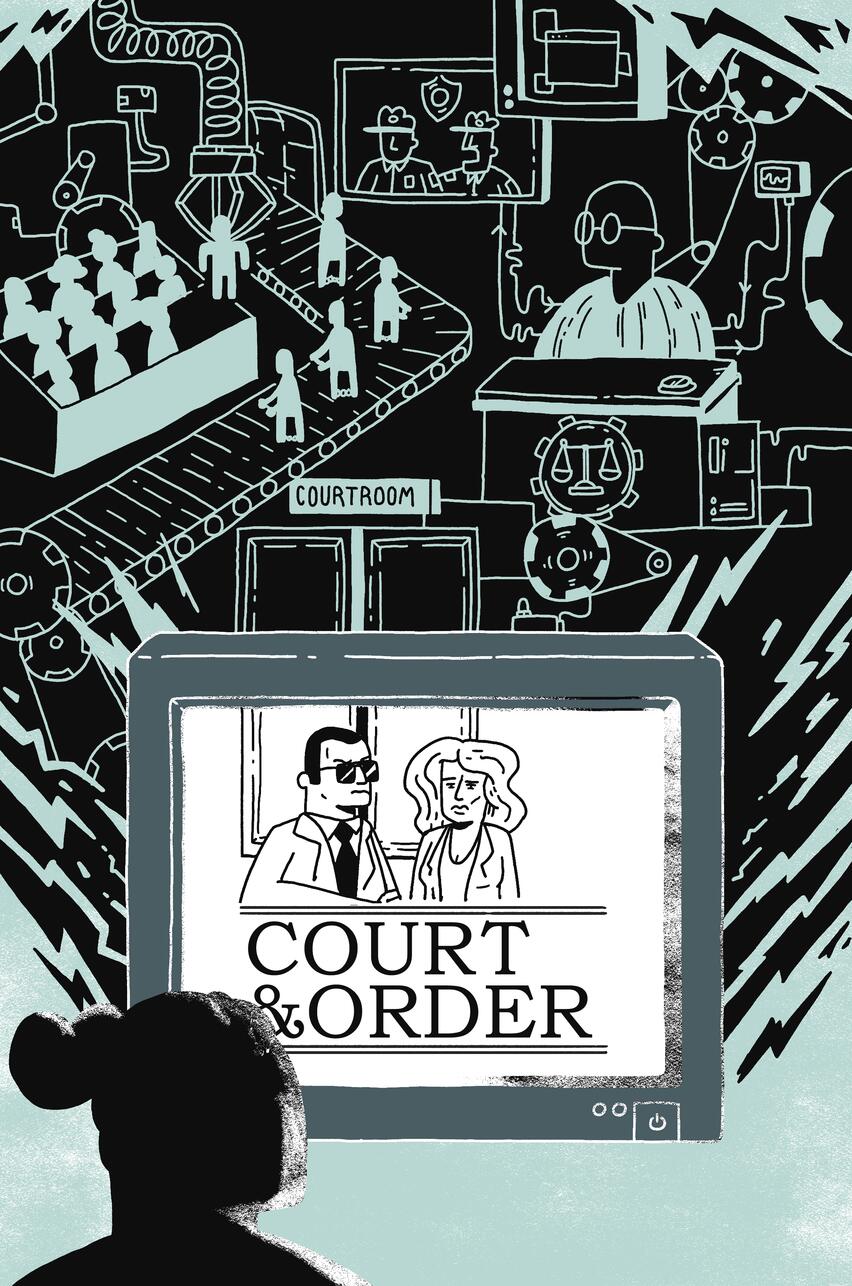

If you have ever seen a TV show or movie about a court case, you are familiar with trials - or at least a sensationalized version of them. In popular culture, when someone is arrested and accused of a crime, they almost always end up in a courtroom, with judges and a jury, fighting the charges against them.

Illusion:

Trials are frequent occurrences. Everyone has a right to trial which means that accused people must get their day in court.

Reality:

Although trials are prevalent in the popular imagination, they do not occur in over 90 percent of cases.

Illusion:

Trials are the moment for the person accused to finally tell their truth, and vindicate their side of the story.

Reality:

Trials are very scary for the person accused. Judges make decisions about what questions can be asked of the witnesses, including the person being prosecuted if they are testifying. Many judges allow prosecutors to ask about their prior criminal record if the person being prosecuted decides to testify in their trial. The potential trauma of being cross-examined by the prosecutor can be a deal breaker in itself. These factors create a strong disincentive for persons accused to tell their side of the story.

Additionally, because so much behavior is criminalized, many people accused of crimes cannot claim innocence according to the law. The criminal legal system is designed to ensure convictions, and thus not every charge has an equally winnable legal strategy. This makes it not worth the risk of lengthy incarceration for the person being prosecuted to share their story, even if they feel it can and should vindicate them.

Illusion:

The person who is being prosecuted and their defense lawyer only think about the trial when they get to that stage of the case.

Reality:

The defense is accounting for what might happen in a trial from the moment the official charges are announced.

Throughout the entire case, the way the person being prosecuted and their lawyer make decisions is about predicting how the trial will likely go, and often those predictions are not hopeful. A lawyer’s advice to her client will hinge on what will happen at trial. The lawyer’s assessment of how likely it is that they will win at trial shapes whether or not to take a plea, and what plea to take.

Illusion:

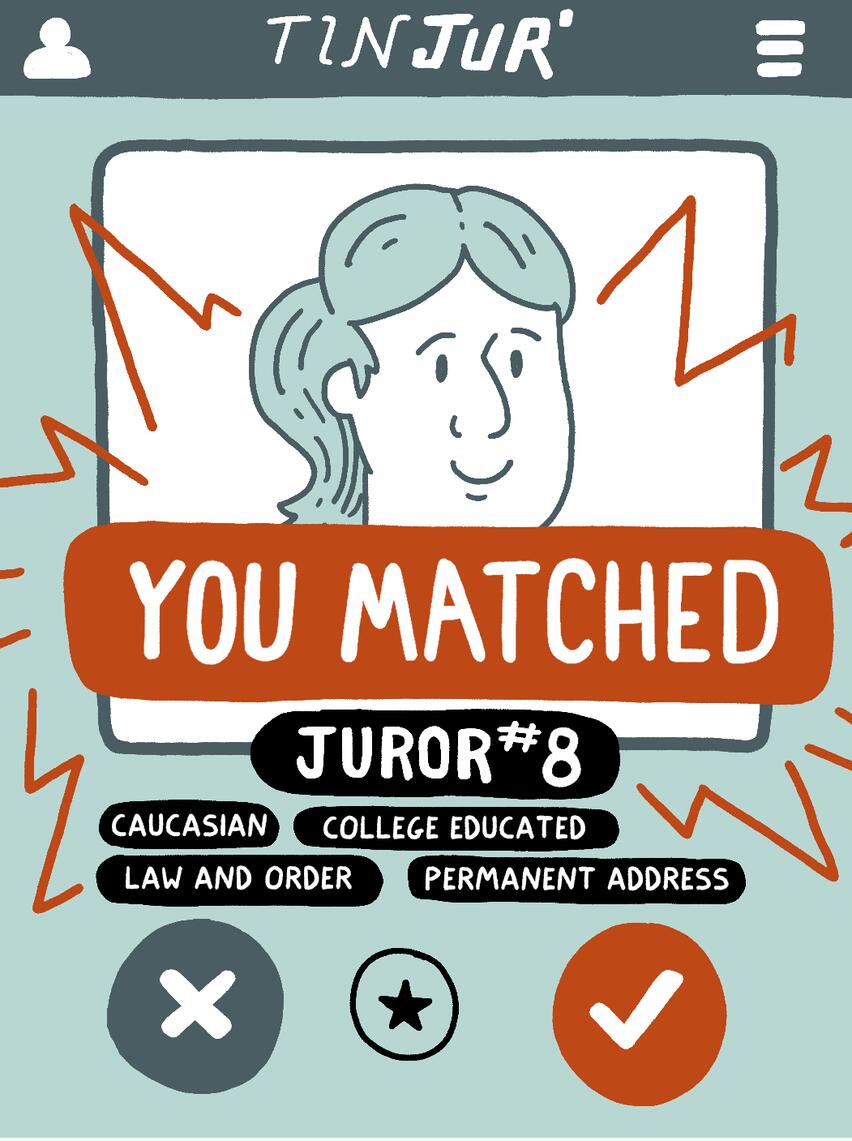

The constitution entitles every person accused to a jury of their peers.

Reality:

Prosecutors consistently prefer white middle-class or upper-class juries. And depending on the jurisdiction, prosecutors can easily orchestrate that composition.

Gentrification changes the demographic composition of who resides in a jurisdiction. People who have stable housing are more likely to actually receive the notice summoning them to jury service. Poverty leads to displacement and changes of addresses. People with stable employment, and who are paid for jury services or who can afford to take time off, are more likely to actually show up.

In addition, people with convictions are disqualified from jury service in many jurisdictions, which disproportionately eliminates jurors of color. Non-citizens and youth are not allowed to serve. Courts do not consistently make accommodations for people with disabilities to be able to serve. Often times people with moral convictions about the criminal punishment system (for example, mistrusting the police or thinking the system is racist) will get disqualified from being on a jury, due to their supposed impartiality, even though in practice their moral convictions may not prevent them from being able to evaluate evidence in an unbiased way.

Serving on a jury is an exercise in empathy. Who do you identify with: the accused person or the prosecution? If no one on the jury has had an interaction with the police that leads them to doubt law enforcement, then the jury will more likely convict. If the jury is able to entertain some doubt about the prosecution’s case, then it may be more likely to acquit. The life stories and socio-economic and political positions of the members of the jury can alter the path of trial.

Here is one example of how different juries impacted the outcome of the case:

Audrey Pischal was a juror on a murder case with two co-defendants in California. She, and other jurors in her group, were convinced one of the co-defendants was innocent. The case ended in a mistrial.

After the mistrial, the other co-defendant took a plea deal while the person Audrey thought was innocent went to trial with another jury. With this new jury, despite no new evidence being shown, he was found guilty and sentenced to life without parole, also known as death by incarceration.

You can read Audrey’s full accounting of her experience here. A new jury with different people resulted in a radically different, and devastating, outcome.

Illusion:

Jurors listen to each witness objectively and uniformly.

Reality:

The prosecution’s star witnesses are police officers, and in general most jurors (considering the kinds of people who are typically selected) trust the police. Meanwhile, because poor communities and Black and brown communities are disproportionately criminalized, witnesses for the defense tend to be poor people of color.

The ways in which communities of color are policed also means that even though defendants may want to call their family members or friends as witnesses, potential witnesses may themselves have criminal records or prior arrests, which the prosecutor can exploit to call into question their testimony. Implicit and explicit bias tends to discount their testimony.

Key takeaways

- The system is designed to ensure convictions through plea deals. It cannot accommodate everyone who is charged, taking their case to trial.

- Less than 10 percent of people accused of crimes exercise their constitutional right to trial because the risk of losing at trial is so great and the penalties for losing in trial, versus taking a plea bargain, can be so extreme.

- Jury composition can determine the outcome of a case and jurors selected to serve are more likely to be white, middle to upper class, and politically moderate to conservative.

- Trials are key moments in participatory defense campaigns - reach out to community to come to court to show the person charged and the court that the community does not support prosecution, and has many other ideas about how to prevent, interrupt and heal from the harm involved. More on participatory defense here.