Plea Bargain

For more information about plea bargains, visit Criminal Court 101: Plea Negotiations & Bargain.

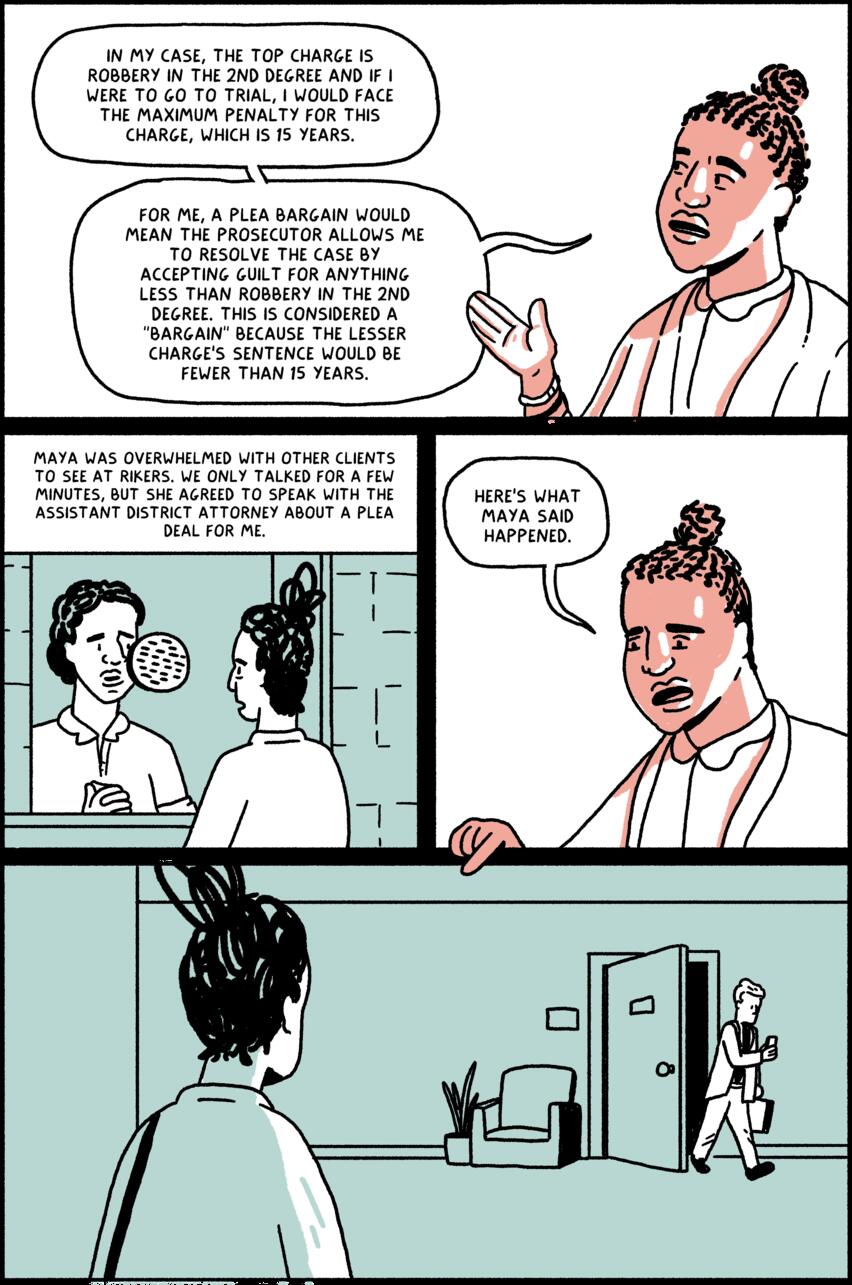

Now in the Plea Bargain stage of the case, Esther narrates, describing the advantages of a plea deal. “In my case, the top charge is Robbery in the 2nd Degree and if I were to go to trial, I would face the maximum penalty for this charge, which is 15 years. For me, a plea bargain would mean the prosecutor allows me to resolve the case by accepting guilt for anything less than Robbery in the 2nd Degree. This is considered a “bargain” because the lesser charge’s sentence would be fewer than 15 years.” “Maya was overwhelmed with other clients to see at Rikers.” Esther and Maya sit in a visitation room on Rikers. They are separated by a plane of plexi-glass, speaking through a small vent in the glass. Present-day Esther sums up the quick conversation. “We only talked for a few minutes, but she agreed to speak with the Assistant District Attorney about a plea deal for me. Here’s what Maya said happened.” A panel shows Maya walking down a courthouse hallway. She spots the Assistant District Attorney, who is prosecuting Esther’s case. He is walking out of an office door, looking at his phone.

Maya walks fast to catch up with the ADA. She shouts out: “Excuse me!” She reaches the ADA and he looks up from his phone at her. “Can we talk about Esther Pierre’s Case?” Maya asks. The attorney begins walking away, holding his phone up to his ear to take a call. He tells Maya, “I’m obviously on my way somewhere and I don’t have time to talk. Plus, I would need her file in front of me.” A panel shows Maya standing alone. She rolls her eyes at how the ADA ignored her. A little squiggle of frustration floats above her head The ADA looks back at Maya from a distance. “Tomorrow, in my office,” he offers.

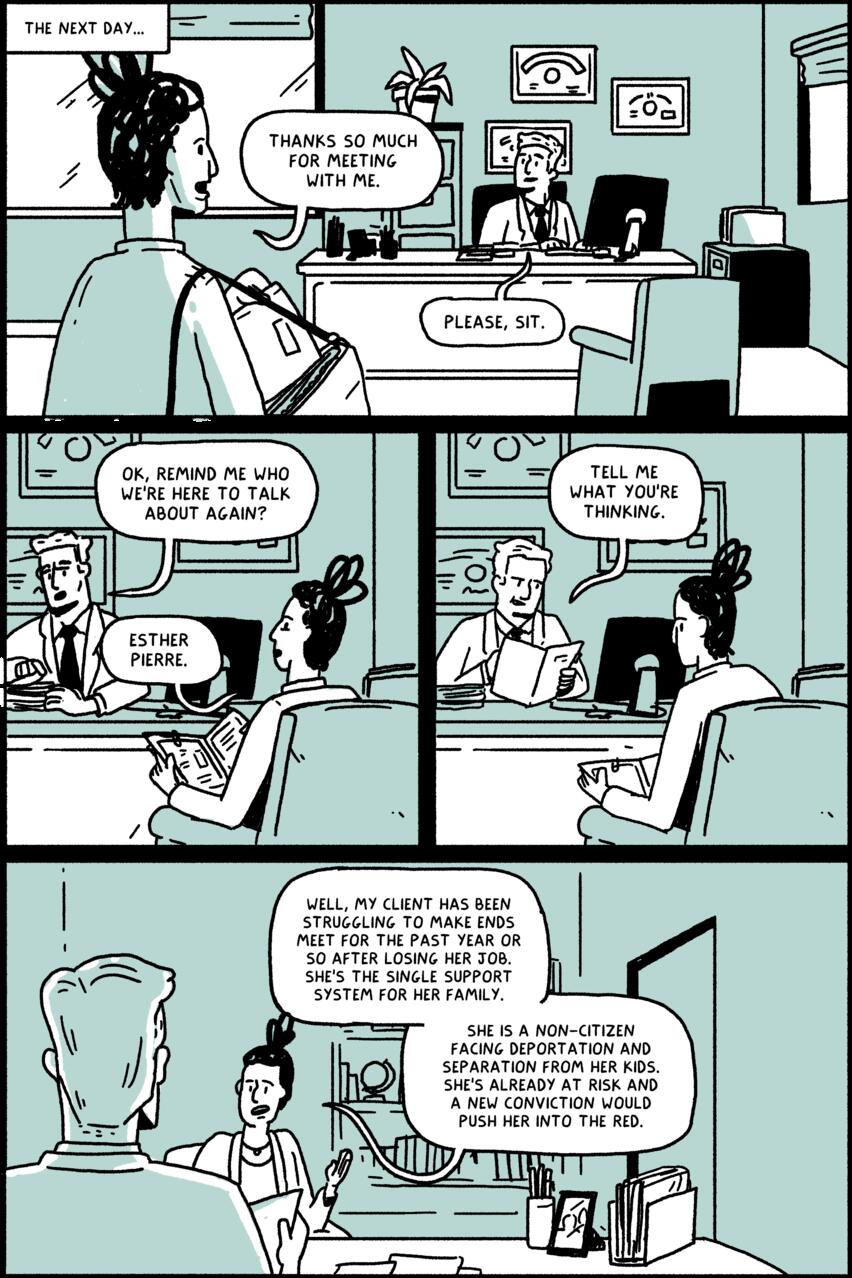

The next day, Maya comes to the ADA’s office. The ADA sits at his desk, working on a computer. Behind him are file cabinets, a small office plant, and diplomas hung on the wall. Maya takes a file out of her bag as she says, “Thanks so much for meeting with me.” “Please, sit,” the ADA responds. Maya sits in a chair opposite the ADA and opens her file. The ADA searches through a stack of folders on his desk. “Ok, remind me who we’re here to talk about again?” he asks. “Esther Pierre,” Maya reminds him. The ADA opens the correct folder and says, “Tell me what you’re thinking.” Maya discusses the context for Esther’s situation. “Well, my client has been struggling to make ends meet for the past year or so after losing her job. She’s the single support system for her family. She is a non-citizen facing deportation and separation from her kids. She’s already at risk and a new conviction would push her into the red.”

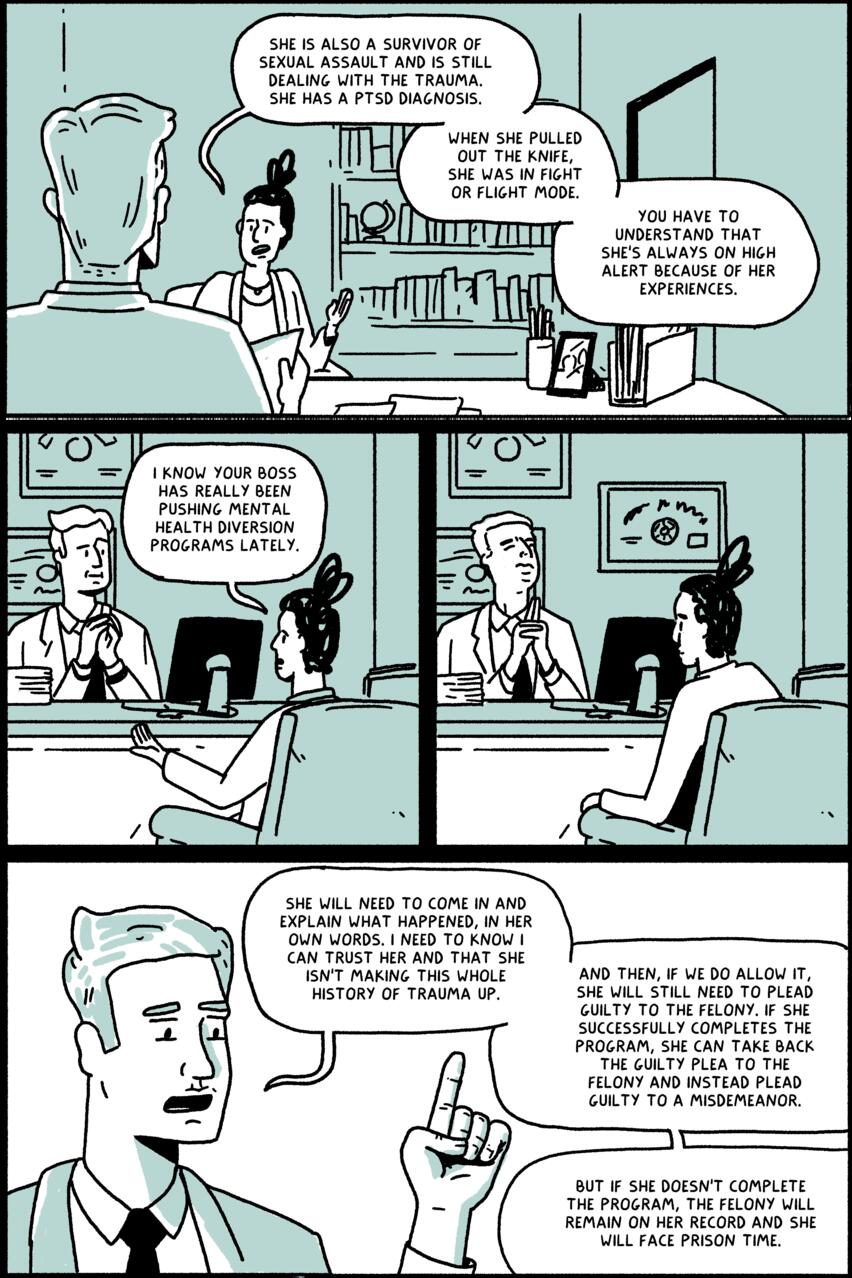

Maya continues explaining Esther’s situation, saying. “She is also a survivor of sexual assault and is still dealing with the trauma. She has a PTSD diagnosis. When she pulled out the knife, she was in fight or flight mode. You have to understand that she’s always on high alert because of her experiences. I know your boss has really been pushing mental health diversion programs lately.” Maya pauses, and the ADA takes a deep breath. He clasps his hands and looks at Maya, then says, “Your client will need to come in and explain what happened, in her own words. I need to know I can trust her and that she isn’t making this whole history of trauma up. And then, if we do allow it, she will still need to plead guilty to the felony. If she successfully completes the program, she can take back the guilty plea to the felony and instead plead guilty to a misdemeanor. But if she doesn’t complete the program, the felony will remain on her record and she will face prison time.”

Maya considers the ADA’s offer. “It’s going to be very difficult for her to come and relive everything she’s been through,” Maya says with a forlorn look. Maya asks, “Can she put it in writing instead? I could give you access to some of her medical records to corroborate?” The ADA closes his eyes and resolutely tells Maya, “No.” “The policy in our office is that if a person wants a program on a violent felony, we need to vet things ourselves. If she does something to someone after we’ve released her, we’ll pay the price and be held responsible. We need to do our due diligence. We have a duty to protect other New Yorkers. And I don’t wanna end up in the New York Post for this.” Maya starts to get up from her chair. She shakes the ADA’s hand and says, “Ok. Thanks for considering. I’ll follow up with you later this week.”

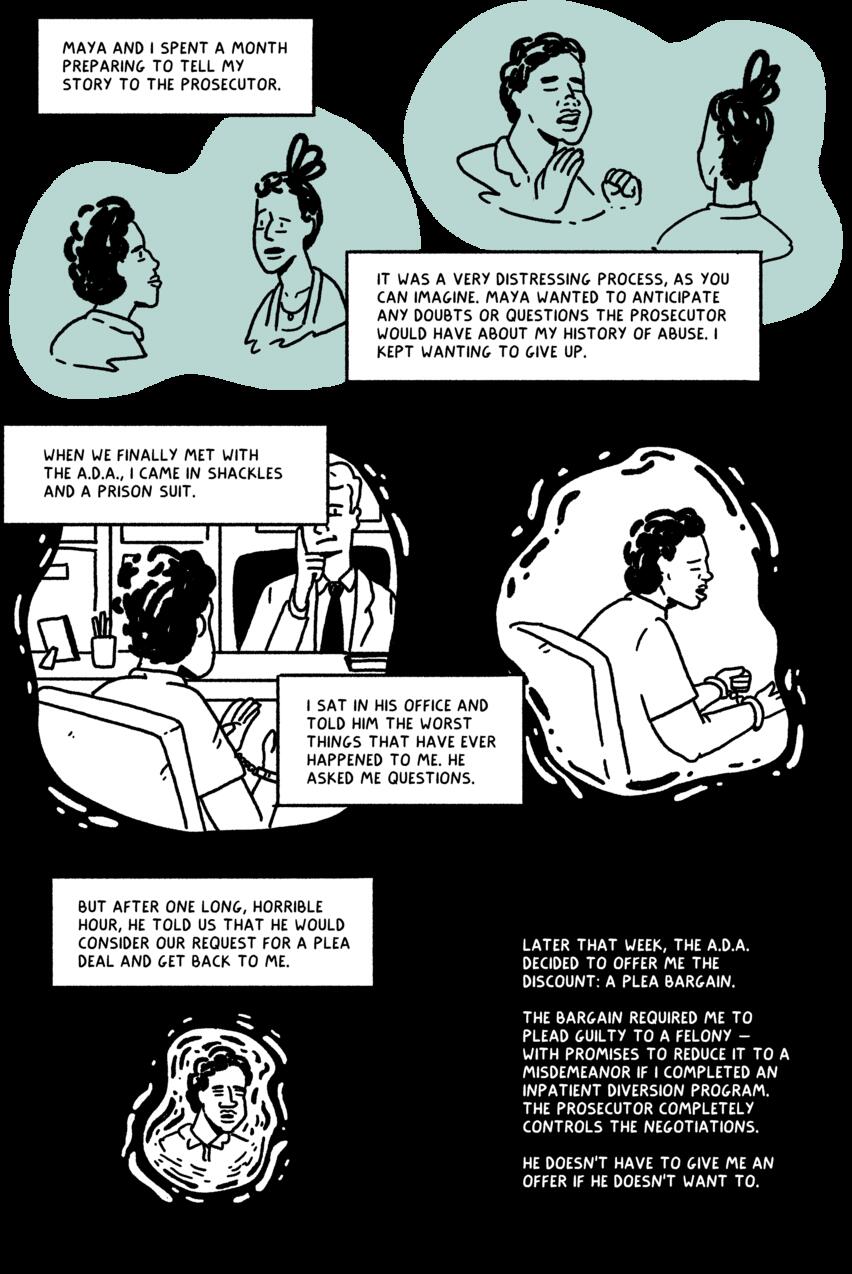

Now, Esther begins narrating her experience again. She recounts what happened after the meeting with the A.D.A.. Drawings show Maya and Esther in deep discussion. “Maya and I spent a month preparing to tell my story to the prosecutor. It was a very distressing process, as you can imagine. Maya wanted to anticipate any doubts or questions the prosecutor would have about my history of abuse. I kept wanting to give up.” “When we finally met with the A.D.A., I came in shackles and a prison suit.” The scene shifts to the ADA’s office. Esther sits in a chair in front of the ADA. A circle of black begins to encroach the scene. “I sat in his office and told him the worst things that have ever happened to me. He asked me questions.” A panel shows Esther emotionally telling her story. The black circle encroaches further upon, and the A.D.A. is no longer visible in the frame. Esther continues. “But after one long, horrible hour, he told us that he would consider our request for a plea deal and get back to me.” The panel shows black has almost consumed a drawing of Esther. Only her face, shaken and distressed, is still visible. The next panel is completely black. Esther’s narration continues in white text. “Later that week, the A.D.A. decided to offer me the discount: A plea bargain. The bargain required me to plead guilty to a felony - with promises to reduce it to a misdemeanor if I completed an inpatient diversion program. The prosecutor completely controls the negotiations. He doesn’t have to give me an offer if he doesn’t want to.”

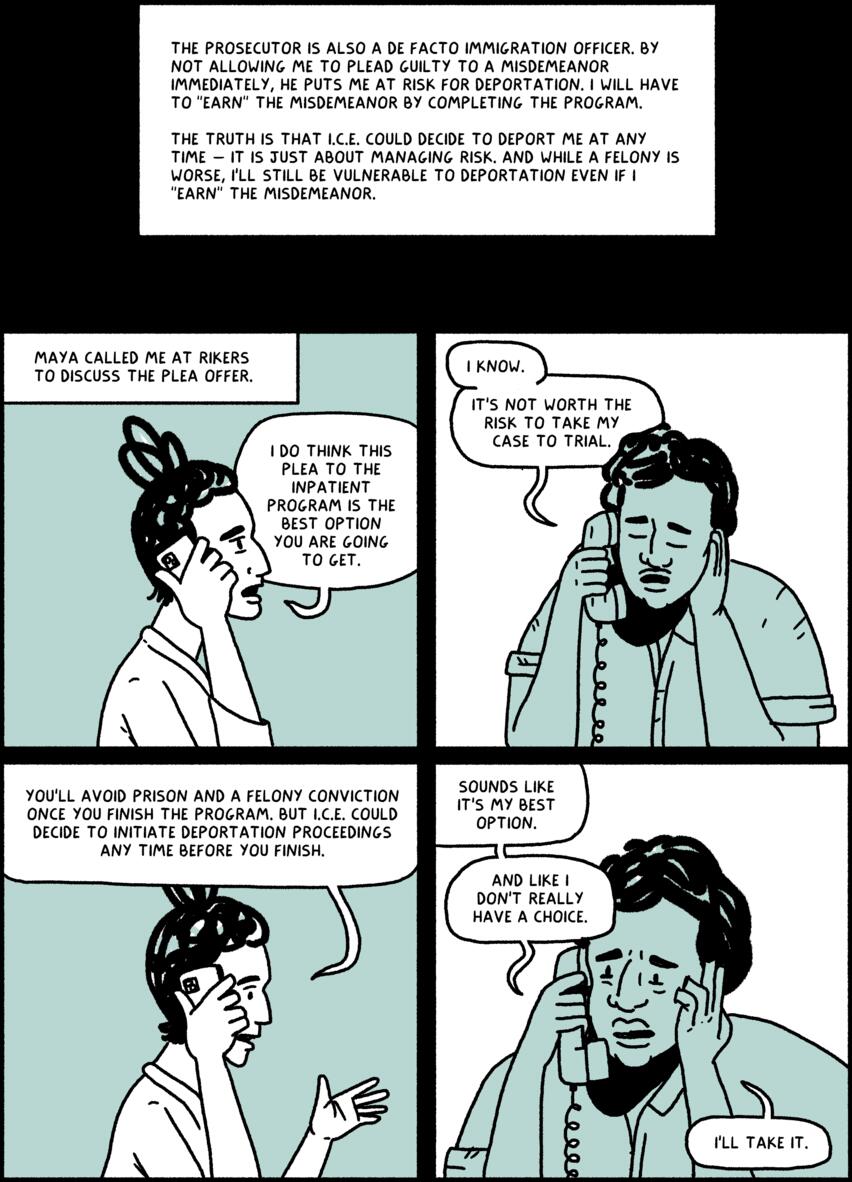

The blackness of the previous panels has subsided. Esther continues narrating. “The prosecutor is also a de facto immigration officer. By not allowing me to plead guilty to a misdemeanor immediately, he puts me at risk for deportation. I will have to “earn” the misdemeanor by completing the program. The truth is that I.C.E. could decide to deport me at any time - it is just about managing risk. And while a felony is worse, I’ll still be vulnerable to deportation even if I “earn” the misdemeanor.” “Maya called me at Rikers to discuss the plea offer.” A panel shows Maya talking on her cell phone. She tells Esther, “I do think this plea to the inpatient program is the best option you are going to get.” Esther is seen talking on a landline phone at Rikers. Her eyes closed and one hand propped on her face, she tells Maya, “I know. It’s not worth the risk to take my case to trial.” Maya elaborates, telling Esther, “You’ll avoid prison and a felony conviction once you finish the program. But I.C.E. could decide to initiate deportation proceedings any time before you finish.” Esther’s face is strained. Her fingers grasp her face and hair in distress. Unhappy with the outcome and worried about her future, Esther tells Maya, “Sounds like it’s my best option. And like I don’t really have a choice. I’ll take it.”

From the present, Esther narrates the specifics of the plea deal offered by the prosecution. “In my case, although the prosecutor offered me the inpatient program - or what is called “diversion” - a judge actually makes the decision about whether or not I can be accepted into the program. The judge also decides the details of the program: How often I need to check in with the court, how long I need to be in the program, etc., etc.” A panel shows Esther and Maya meeting with a social worker. The social worker is a younger woman wearing a button down shirt. Her black hair is cut in a bob. Maya shakes the social worker’s hand as Esther narrates: “There are many steps before I can even get accepted into the program. Before I saw the judge, I had to be screened by social workers who work for the courts. Those social workers help the judge decide whether I am eligible for treatment. I made the trip from Rikers to the court many times during the process.” Now, Esther sits in a chair at the social worker’s desk. Behind them is a large window looking out onto the Brooklyn street below. The social worker hands Esther a form and tells her, “First, I’m going to need you to sign these forms that give the court access to your medical records.” She sits and tells Esther, “We need to look at those to confirm that you do actually have a diagnosis under the D.S.M.-5. You must have an official diagnosis to be accepted into the program.” Esther starts filling out the form with a pen. She tells the social worker, “Yes, I do. I’ve been diagnosed with P.T.S.D.”

The social worker elaborates. “Well, we still need to check. Okay, so I have looked at your criminal record. You have a past misdemeanor conviction - for drugs I see. That’s fine. You don’t have a history of violence, which is good. Judges don’t tend to accept people with histories of violence, especially given that you are charged with a violent crime right now.” Esther narrates from the present, saying, “The social worker then asked me a series of questions about my medical and personal history. She was looking for any discrepancies between what I told her about my past, and what she gleaned from my records.” A panel shows Esther and the social worker in silhouette against the light of the window. Buildings across the street and further off in the skyline are visible outside. The social worker explains the details of the program. “The Good Samaritan Drug and Mental Health Program works like this. You will need to participate in the program for at least 2 years. In the beginning, you will have to live in the residential facility of the program. You will have to abide by the program’s curfew and code of conduct.”

A panel shifts the scene outside, to the street below the window. A construction lot across the street sits empty. Cars are parked along the curb. A street vendor is set up with a cart serving Italian Ice. A mom buys her son a treat from the vendor. Over top of the drawing, the social worker continues explaining. “You won’t be able to do whatever you want to do. This won’t be like you’re just going home. In fact, you won’t be able to live at home with your children until you complete the first portion of the program. You will have to submit to regular drug tests. You will have to come to court on a monthly basis with a social worker from the program to report to the judge about your progress. You will need to meet with a therapist and also attend group therapy.” A drawing zooms in on the street vendor. The mom hands the vendor some money as her son takes a lick of the treat. The social worker asks Esther, “Are you willing to comply with all of these expectations?”

A panel shows Esther looking out the window at the scene below, distracted by the everyday-ness of other people’s lives while she sits trapped inside the social worker’s office. In the next panel, Esther is in silhouette as her attention comes back to the question at hand. She tells the social worker, “I suppose… If I have to…” She pauses, then agrees. “Yes.” “Are you sure?” the social worker asks. The panel shows the two seated across from each other. Esther looks tired and unsure of herself. “You seem a bit resistant,” the social worker says. “We can only recommend you to the judge if you have no hesitation about participating and if you are willing to take responsibility for your crime.” A panel shows a close-up of Esther’s face. She forces a semi-confident smile. “Yes, sorry. Absolutely,” she tells the social worker. “I’ll do whatever it takes. I’m very eager to participate in this program. I take full responsibility for what I did.” From the present, Esther explains her decision. “I said what I needed to say, but really I was very anxious about all that the program required. It was better than prison, sure, but two years was still a long time to be under the watchful eye of the courts.” The plea bargain section of Esther’s story ends here.