Sentencing

For more information about sentencing, visit Criminal Court 101: Sentencing.

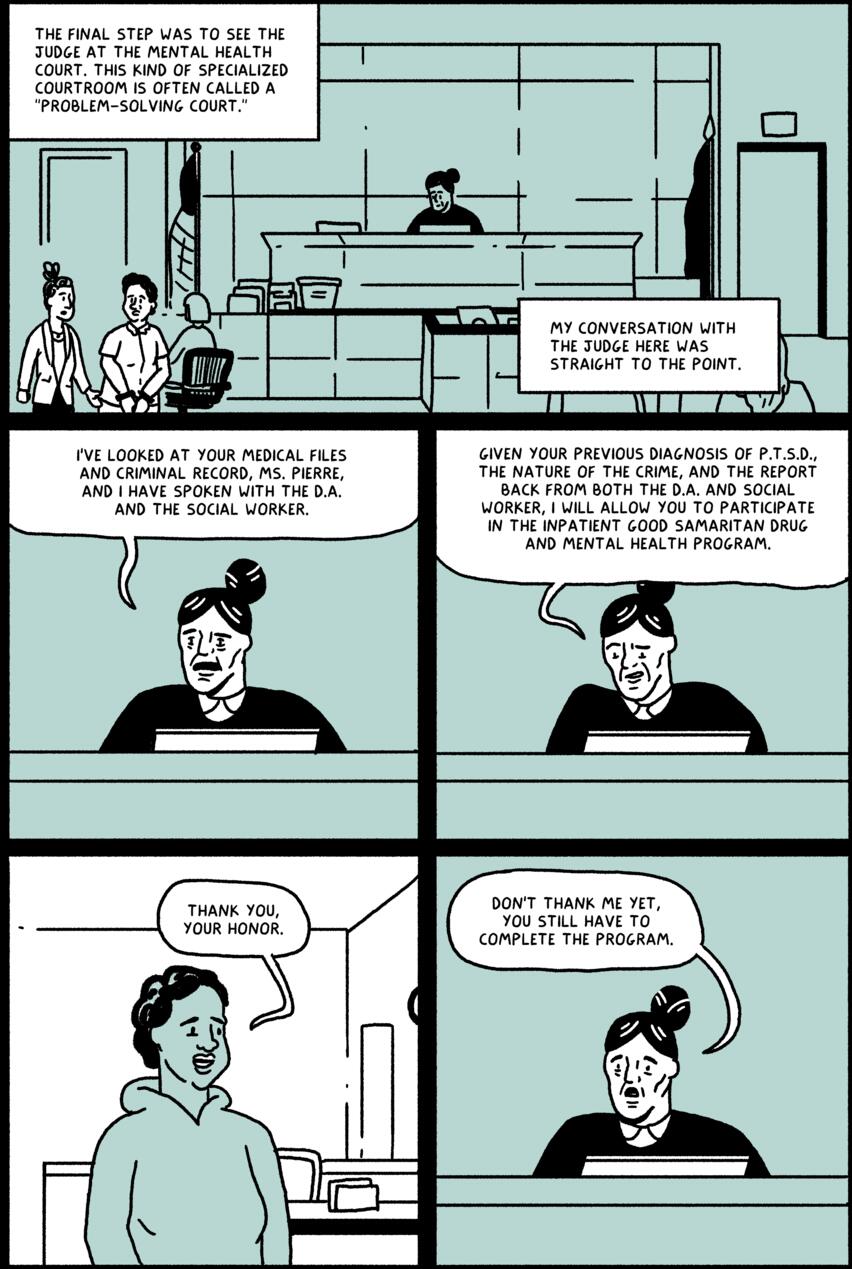

This final section describes the sentencing phase of Esther’s case. A panel shows a new courtroom. The judge, an older woman with her dark hair in a bun, sits at the dais. Court workers sit and prepare for the hearing. Esther and Maya are walking into the room as Esther narrates the events. “The final step was to see the judge at the mental health court. This kind of specialized courtroom is often called a ‘problem-solving court.’ My conversation with the judge here was straight to the point.” A panel depicts the judge sitting at her dais. She tells Esther, “I’ve looked at your medical files and criminal record, Ms. Pierre, and I have spoken with the D.A. and the social worker. Given your previous diagnosis of P.T.S.D., the nature of the crime, and the report back from both the D.A. and social worker, I will allow you to participate in the inpatient Good Samaritan Drug and Mental Health Program.” A panel shows Esther standing in the courtroom. She tells the judge, “Thank you, your honor.” Don’t thank me yet,” the judge replies. “You still have to complete the program.”

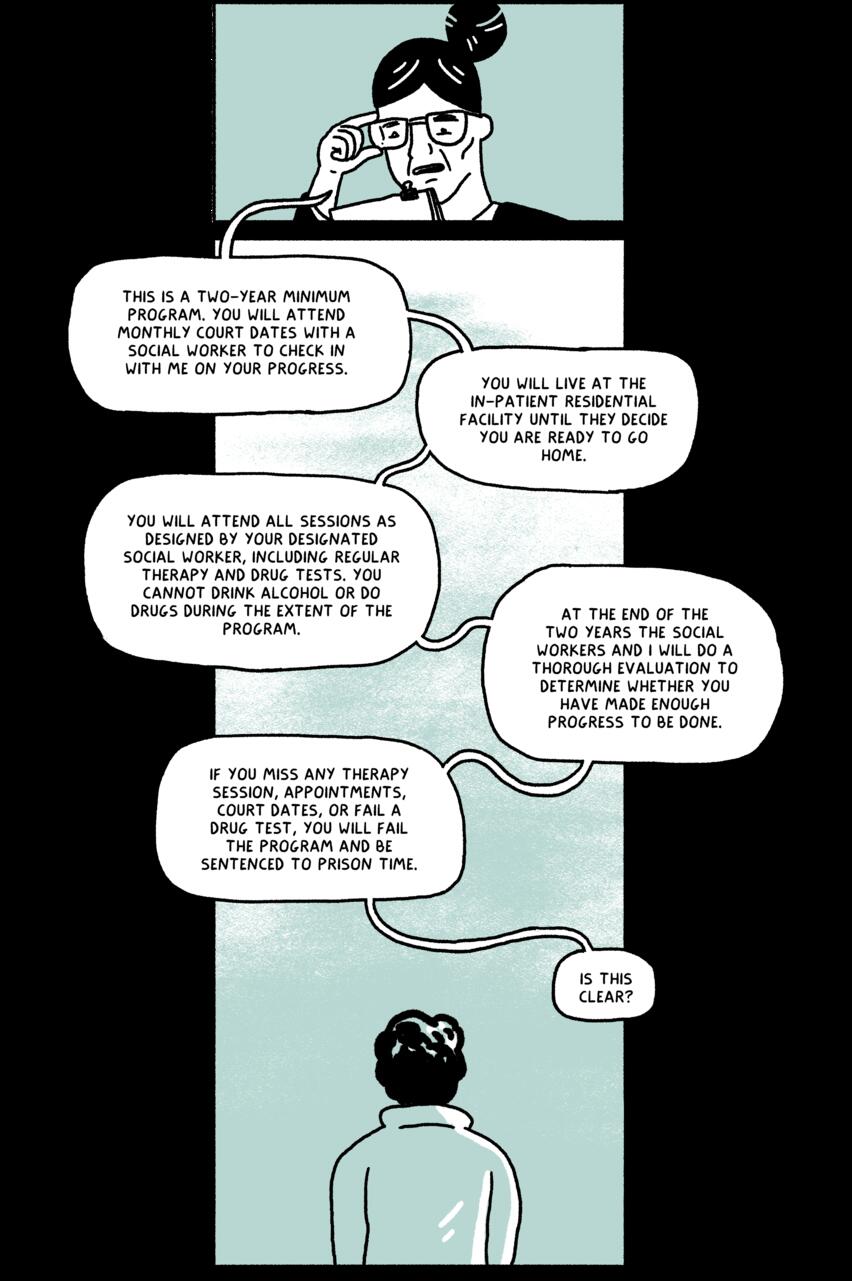

A panel shows the judge closer now. She puts on her glasses and reads from a piece of paper. “This is a two-year minimum program,” she says. “You will attend monthly court dates with a social worker to check in with me on your progress.” A long, vertical panel leads down to show Esther from the back as she looks up at the judge. The judge’s description of the program continues in word balloons that cascade down the page, coming to rest just above Esther’s head. “You will live at the in-paitent residential facility until they decide you are ready to go home. You will attend all sessions as designed by your designated social worker, including regular therapy and drug tests. You cannot drink alcohol or do drugs during the extent of the program. At the end of the two years the social workers and I will do a thorough evaluation to determine whether you have made enough progress to be done. If you miss any therapy session, appointments, court dates, or fail a drug test, you will fail the program and be sentenced to prison time. Is this clear?”

Esther — still seen from the back, looking up at the judge — responds. “Yes, your honor.” The judge concludes the hearing, saying, “Court is adjourned for six weeks for Ms. Pierre to enter into the plea agreement.” A large panel is filled with black, grainy texture. Against the black, Esther’s narration continues. “Six weeks later, I am taken back to court to take the guilty plea in exchange for participating in the program.” In the black texture, the voice of the judge calls to Esther. “Ms. Pierre, I understand that you want to plead guilty.” “Yes,” she replies

The judge, shown in profile, speaks directly to Esther. She tells Esther, “The prosecutor has charged you with: Robbery in the 2nd Degree, Assault in the 2nd Degree, Criminal Possession of a Weapon in the 2nd Degree. Instead of going to trial, the prosecutor has made a plea offer to you: You can plead guilty to Attempted Assault in the 2nd Degree in exchange for the chance to participate in the diversion program. If you successfully complete the program, you can withdraw your plea and enter a plea to a misdemeanor. If you do not complete the program, the felony conviction will remain on your record permanently and you will have to serve prison time. Is that what you want to do?” Esther — also shown in profile and facing the judge — responds. “Yes.” The judge asks Esther, “Have you had the opportunity to consult with your attorney about possible defenses you might be giving up by not going to trial on these charges?” Esther responds. “Yes.”

This image consists only of dialog balloons which start at the top edge of the panel and meander downward. The judge’s questions and Esther’s responses weave alongside each other. “Do you understand that if you plead guilty you are giving up your right to a trial?” the judge asks. “Yes.” Esther says. “Do you understand if you plead guilty you are giving up your right to cross-examine witnesses?” “Yes.” “Do you understand if you plead guilty you are giving up your right to testify or remain silent?” “Yes.” “Do you understand that there may be immigration consequences if you accept this plea, including deportation or denial of naturalization?” “Yes.” “Is it true that, on November 20, 2018, you attempted to injure someone in the Duane Reade in Downtown Brooklyn?” “Yes.” “And is it true that you used a weapon? A knife?” “Yes.” “Besides the promise of a program and a misdemeanor, has anyone promised you anything else in exchange for this plea?” “No.” “Has anyone coerced you to plead guilty?” “No.”

The judge and Esther, both in profile, face each other now. The judge asks, “Are you pleading freely and voluntarily?” “Yes.” Esther says. Now, the judge reads Esther’s sentence. “The sentence of the court is the Good Samaritan Drug and Mental Health Program. You will have to abide by the terms of the program for a minimum of 2 years to completion. You will have to submit to regular drug tests and report to the court. Any violations of the rules of the program, or any arrests will bring you before this court. I will then decide whether you can remain in the alternatives to the incarceration program. If I find that you are non-compliant or that have been expelled from the program, I will sentence you to prison time. Do you accept the terms of the plea? If so, please sign the contract in front of you. Do you accept the terms of the plea? If so, please sign the contract in front of you.” “Ok,” Esther says. The panel shows a close-up of Esther’s hand signing her name on the contract. The judge finishes her sentence, saying, “The case is adjourned to September 20, 2019, for your first update.”

Present-day Esther narrates what happened after her sentence was read. “After I took the plea, they removed my handcuffs. I only had a few minutes to quickly hug my children. The social workers were at my court date and they took me from court to the resident, in-patient facility. This is the first part of the sentencing, where I accept to enter a program. But that doesn’t mean the case is over or that my sentencing is over. My sentence is completing the program and remaining under supervision until I do. If and when I do, I come back to court for the judge to officially declare that I will have completed my sentence. I was under the control of this program for the next two years. What is true about diversion and alternative to incarceration (ATI) programs - and other forms of supervision or monitoring - is that they replicate the same dynamics of incarceration and they extend carceral control outside the prison into the community. Even after I was able to leave the in-patient residential program and return home, I still had a curfew and had to attend daily counseling sessions. If I did not attend sessions, refused to take medications, or got into an argument with staff or other participants, I could be sanctioned by the program. A sanction could have set my progress back and require me to be there longer than the two years. If I acquired too many sanctions, the judge could have expelled me from the program and I would have had to serve the prison sentence and the felony would have remained on my record. I watched this happen to other people who were at the treatment program at the same time as me.”

Esther continues describing her experience in the program. “While I did receive a few minor sanctions for having to miss a couple sessions, I was able to stay in good favor with the judge and successfully completed the program in the two-year period. At my final court date, the judge allowed me to take back my guilty plea to the felony and plead guilty to a misdemeanor. My sentence was “time served” which means I had already completed the sentence because I had completed the program and there was nothing left for me to do. However, my now two misdemeanor convictions still hang over my head in the sense that I am more vulnerable to deportation. Less vulnerable than I would be with a violent felony conviction, but more vulnerable than if I didn’t have any criminal record. My criminal record, even just with misdemeanor convictions, also makes finding jobs, securing housing, and accessing public benefits much more difficult.” A panel shows Esther back in the organizer’s meeting room, as she was at the beginning of the story. She continues to tell the crowd her story. “My case may have ended but the collateral consequences won’t ever go away.”

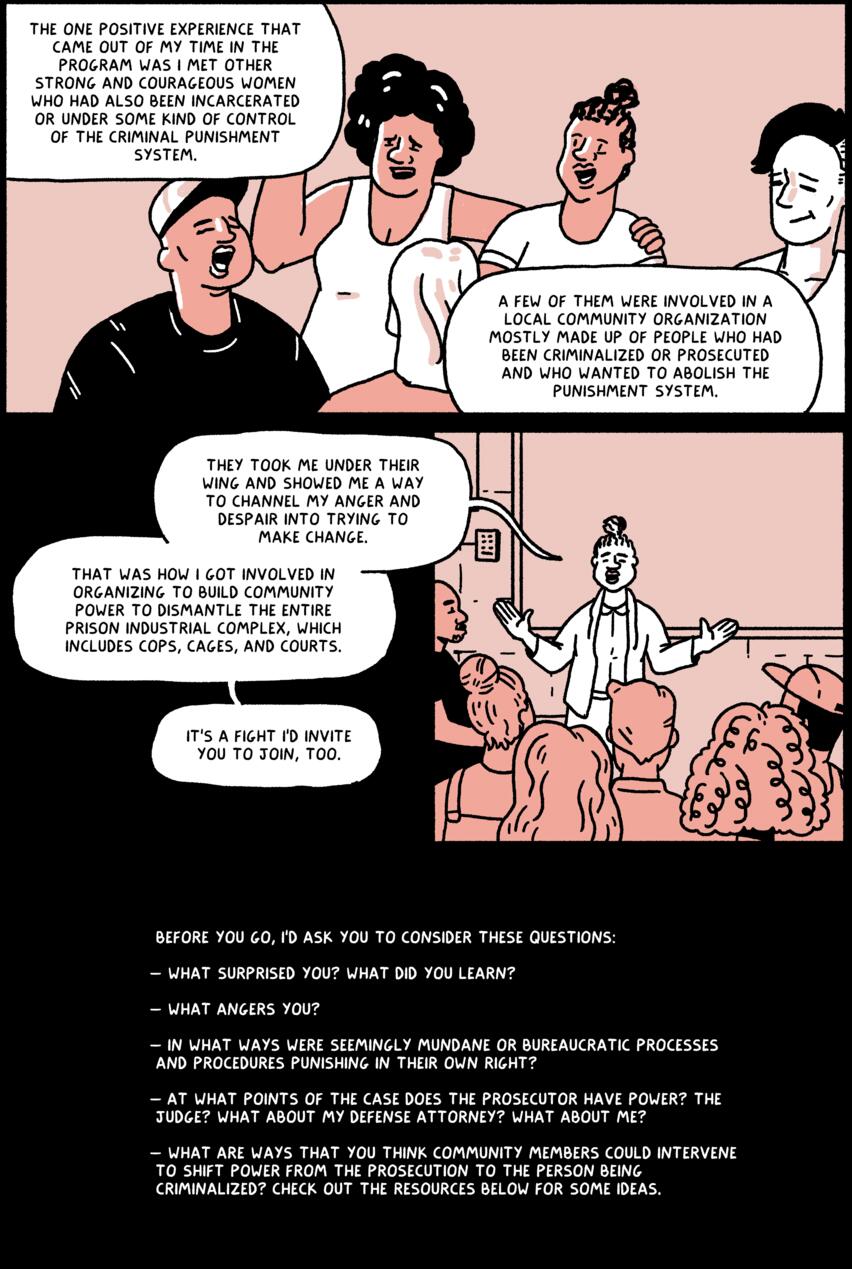

“The one positive experience that came out of my time in the program was I met other strong and courageous women who had also been incarcerated or under some kind of control of the criminal punishment system.” A panel depicts Esther among a group of femme-preesenting oorganizers. One of them, a dark-skinned woman with a short afro, has a hand on Esther’s shoulder. They are all smiling and laughing. Esther continues narrating. “A few of them were involved in a local community organization mostly made up of people who had been criminalized or prosecuted and who wanted to abolish the punishment system.” “They took me under their wing and showed me a way to channel my anger and despair into trying to make change. That was how I got involved in organizing to build community power to dismantle the entire prison industrial complex, which includes cops, cages, and courts.” A panel shows Esther wrapping up her story at the organizer’s meeting. She puts her hands out to welcome the crowd into the struggle. It's a fight I’d invite you to join too,” she says. Before you go, I’d ask you to consider these questions: What surprised you? What did you learn? What angers you? In what ways were seemingly mundane or bureaucratic processes and procedures punishing in their own right? At what points of the case does the prosecutor have power? The judge? What about my defense attorney? What about me? What are ways that you think community members could intervene to shift power from the prosecution to the person being criminalized? Check out this resource for some ideas. Esther’s Story ends here.